Your boss may have more than just a moral obligation to protect you from a person with a gun who barges into your office.

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA), employers are required to provide a workplace "free from recognizable hazards that are causing or likely to cause death or serious harm to employees."

The rule means many bosses need a violence prevention plan if there had been a foreseeable threat at work. Two common examples of such a threat would be: a domestic violence situation that threatens to enter the office, or a disgruntled employee who has said something that raises concern.

“We as a society expect employers to not be negligent, and not be careless with the lives of its employees,” said Seattle employment lawyer Jesse Wing.

The federal government does not lay out any specific examples of what to do in response to these threats. OSHA makes that explicit on its website: "There are currently no specific standards for workplace violence."

However, Wing said there are some general guidelines in the state of Washington.

“Having a zero-violence policy is a decent starting point,” Wing said, adding: “Educating and involving employees so they're all aware they need to speak up if they see a risk.”

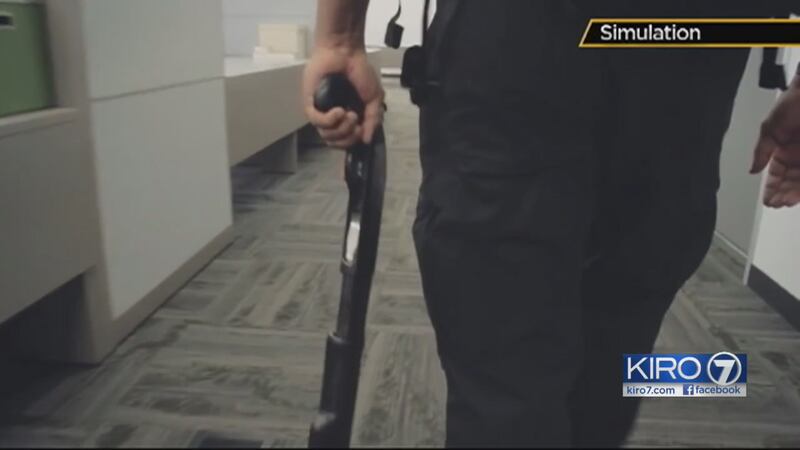

Jesus Villahermosa is a 33-year veteran of the Pierce County Sheriff's SWAT team. He now helps officers and schools come up with specific violence prevention and response plans for active shooter scenarios.

“The problem is that we're a reactive society by nature,” Villahermosa said. “We wait for things to go wrong, and then do something, instead of saying: ‘That happened next door, maybe we should look at doing this.’”

Villahermosa said being proactive with a secure building is a good start. However, he said empowering people to protect themselves is the best plan, especially having workers practice getting behind nearest secure lockable door. He said statistics show shooters do not breach non-glass doors.

The former SWAT team leader also advises that if there is no place to lock down near you, know the quickest way out, even if that means extreme measures like jumping out windows.

Villahermosa said you need to be asking yourself blunt questions: “Can you get out that window? Have you thought about what it would take to break that window if it's a solid pane? Do you have something in the office to break that window?”

Finally, if there are no other options, Villahermosa teaches people they may need to arm themselves with office objects for a fight, essentially becoming their own first responders.

“The cops and the firefighters have it down, we're good at it, but we're not there yet,” Villahermosa said. “Even if my response time is two minutes, it's one minute 59 seconds too long, because I can pull the trigger of a gun every second.”

A side effect of having a proper plan for more likely scenarios like domestic violence and disgruntled workers will end up helping employees through the more unlikely event of a terrorist attack like the one in San Bernardino.

“Understand you are preparing for violence,” Villahermosa said. “It doesn't matter if the basis of the violence is terrorism, or domestic terrorism, or I’m just ticked off at my wife, or I’m just ticked off at my boss.”

In downtown Seattle, armed with new knowledge about the right kinds of preparation offices should be doing, KIRO 7 posed a simple question: What are they doing at your office to prepare?

The answers were varied. One woman said: “Mostly [we’re told] to call for help and assistance.” Another man said: “Keep your eyes open, if you see something unusual in the office building report it.”

Many said employee security was not discussed at all. KIRO 7 only found one man who said his office was being proactive.

“We have active shooter training,” He said. “They tell us to run, hide, or fight back, that type of thing.”

He was a government worker, which may explain why his bosses are so familiar with OSHA's safety requirements.

Cox Media Group