DNA that could link criminals to hundreds of unsolved crimes has gone untested for years in Seattle, despite judges’ orders to enter the samples into an international criminal database.

Most of the cases involve sexually motivated crimes, and nearly all the victims have not been notified.

“It makes me sick to my stomach,” said one of them, who learned of the problem only after KIRO 7 contacted her.

The problem can be solved with simple fix to a state law. Lawmakers have known about the problem since 2015 and have done nothing to fix it. Even if they move forward as quickly as possible, it won’t be solved until the 2017 Legislative session.

Because few people know about the problem -- and because fewer are working to solve it -- authorities worry a fix could be several years away.

Each month, the number of untested DNA samples from convicted criminals grows.

Authorities also worry that not all Washington jurisdictions know about the problem with Seattle cases, meaning additional samples from other cities may not be entered.

“We have these databases for a reason,” Seattle City Attorney Pete Holmes said. “This is the kind of public safety issue that keeps you awake nights.”

Missing links to larger cases

Before King County resident Gary Ridgway was identified as the Green River Killer -- the most prolific American serial killer with 49 known victims and many more claimed – his only criminal history involved arrests for patronizing prostitutes.

Patronizing a prostitute is one of the convictions that now requires a DNA sample – but those samples aren’t being tested in Seattle cases.

%

%

Statewide, the majority of unsolved rapes and murders -- including all Seattle cold case homicides in the last five years -- have been solved with DNA already in the database from lesser crimes.

The database includes more than 250,000 cases from around the world. Most are unsolved.

“It someone was victimized by the same guy while DNA is waiting to be tested, I would be really angry,” one of the untested case victims told KIRO 7. “And I would be really hurt.”

No notification about years-long problem

She was 16 when she first met the man who would stalk her for years. They worked together at a summer job and had a few conversations, but were never close friends. The two didn’t go on dates. She didn’t even know his last name.

“There was no indication he had any infatuation with me,” the woman said.

Two years later when she was away at school, the woman received an email.

“I love you and want to marry you,” one read.

%

%

The sender became more aggressive, sending lewd photos and describing what he wanted to do. After she threatened to call police, she thought the messages stopped. But four months later, the woman found close to 300 message in an old email account -- many graphic -- from the man who couldn’t end his obsession.

“I’m going to find you,” he wrote. “We’re going to be together.”

Seattle police found him first, and the suspect was convicted of cyberstalking. The woman obtained two no-contact orders, and earlier this year the suspect admitted he repeatedly sent graphic photos of himself “with the intent to harass, intimidate (and) torment” her.

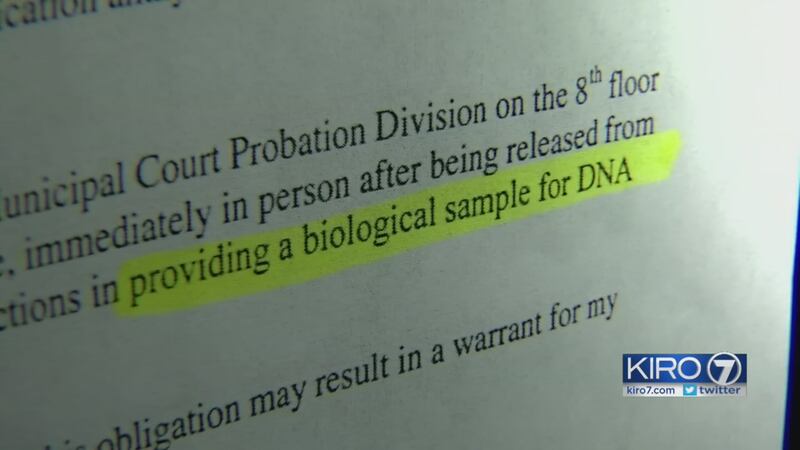

The same day, a judge ordered him to give a DNA sample.

But that sample -- along with more than 100 others from similar crimes – has not been tested in the DNA database.

“I couldn’t eat while this whole thing was going on,” the victim said. “I felt like I couldn’t leave the house for a while.”

“It makes me sick to my stomach knowing he could be getting away with other crimes.”

Code language leads to problem

In Seattle, seven municipal court offenses require offender DNA samples upon conviction: sexual exploitation, violation of a sexual assault protection order, communication with a minor for immoral purposes, stalking, harassment, patronizing a prostitute, and assault with special allegation.

The DNA collection is ordered under state law. But in Seattle, these seven charges come under city law, called the Seattle Municipal Code.

State law and city law describe the same crimes, and court precedent said Seattle cases need to be charged under city law.

But because DNA collection is specified only under state law -- not equivalent city laws -- the Seattle samples are not tested. They haven’t been since 2014, when State Patrol Crime Lab staff noticed the distinction.

There are concerns the problem may also be occurring in other Washington cities.

Inaction from Legislature prolonging problem

After police collect a DNA sample with a court order -- usually taken from inside the mouth with a long cotton swab -- it’s sent to the State Patrol Crime Lab off Airport Way South in Seattle. Each has the convict’s name, the crime, and cites the law that allows for DNA collection.

It was a lab technician who noticed that the seven crimes -- sexual exploitation, stalking, and the others -- were being charged in Seattle under city law instead of state law.

Jean Johnston, the DNA database manager, reached out to the state Attorney General’s Office for clarification, then started communication with the Seattle City Attorney’s Office in 2015.

KIRO 7 obtained emails between the State Patrol crime lab and the City Attorney’s Office -- more than 800 pages -- through a public disclosure request. They show the exceptionally slow pace of the government process.

Specific responses took several business days. Trying to plan meetings took months.

Some people who know about the problem wonder if Holmes’ staff -- including some who are no longer there -- moved as quickly as they could have.

No Seattle city official has even spoken about the problem publicly. As bureaucratic delays continue, the samples remain untested.

“Disappointed is an understatement,” was how City Attorney Pete Holmes felt learning of the problem last year.

%

%

He also points out the complexity that leads to the long delays. The State Patrol Crime Lab staff suggested the seven crimes be charged under the existing state law, but Holmes said that’s not possible after a 2012 State Supreme Court decision.

Holmes wondered if the crime lab could test the samples now while they were waiting for a Legislative solution, but crime lab staff was advised by the Attorney General’s office they could not.

Holmes also would like more clarification on why the samples aren’t accepted now when they were previously, since 2008. He believes samples tested before the problem was recognized in 2014 aren’t in jeopardy of being dismissed.

After more than a year without a solution, the crime lab told the City Attorney’s Office “we can either destroy these samples or you can make arrangements to pick them up.”

The City Attorney’s Office retrieved them, and the number of DNA samples now grows at the Seattle Police evidence unit.

Last month, officers arrested 204 men during a prostitution sting. Any convictions that come from those cases, which included employees of Amazon and Microsoft, would require DNA samples.

But they wouldn’t be tested until the state Legislature solves the sample problem.

“Now at least they are in our possession,” Holmes said of the existing DNA samples. “I have renewed hope that with some public scrutiny here shining a light on this that maybe we will get the attention in the next (Legislative) session.”

Victims, police, city attorney, crime lab staff tired of waiting

The only Legislative fix was attempted as a small part of a house bill, introduced in January 2016.

But even that didn’t address the whole problem -- only a few of the seven crimes were included -- and the overall bill for domestic violence protections died in a Senate committee.

“I don’t think anyone knows that,” attorney Sim Osborn told KIRO 7 of the legal loophole that prevented the DNA from being tested. “I clearly didn’t hear that until I heard it from you.”

His firm has represented several victims of stalking and sexual assaults. He also understands how terrifying incidents can be for victims.

%

%

In 2014, Osborn was walking by the Washington Athletic Club in downtown Seattle when a longtime criminal -- someone known by police for harassing women -- accosted Osborn for money. When the suspect didn’t get it, he appeared to be reaching for a weapon.

“I’ll blow your (expletive) brains out,” he said, according to police. “I’ll put you to sleep permanently.”

Osborn called 911. He was granted a no-contact order, and the suspect was later convicted of harassment. A court order forced the suspect to give a DNA sample.

But police don’t know if that well-known suspect is linked to unsolved crimes.

His case is one of the DNA samples that’s sitting untested.

It will remain there until the state Legislature takes action, and a bill finally corrects the problem that’s been unsolved for years.

Police say they’re sure those samples will solve other crimes.

Victims say they’re tired of waiting.

“At this point, I’m not sure what else we can do other than to seek the Legislative address that we’ve asked for,” Holmes said. “We want to put that evidence into the database.

“I just want to fix the problem.”

Cox Media Group