An icon in the yearslong effort to end racism in the treatment of cancer has died.

The impact this woman had in the 28 years she lived with breast cancer.

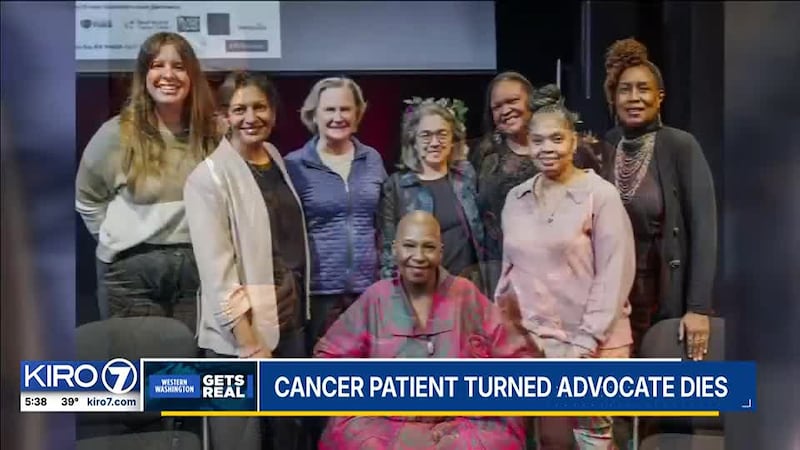

Those who knew Bridgette Hempstead describe her as a warrior for Africa-American women diagnosed with breast cancer.

Hempstead lost her own battle with the disease in December.

She showed the world that cancer patients can live full, productive lives.

To understand Bridgette Hempstead, mother, grandmother, globetrotting breast cancer equity advocate, you just have to listen to her one-time oncologist.

“I had lots of introductions from the community then who said ‘you need to meet this powerhouse,” recalled Dr. Julie Gralow, an emeritus professor in the Clinical Research Division of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. “’She’s forming this African American cancer support group. You guys need to be together.’”

To the diversity chief where she first got treatment and began to fight for herself “and everyone who was underserved,” said Dr. Paul Buckley, chief Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Officer at Fred Hutch. “That was her issue. That was her purpose. That was her commitment.”

And listen to the oldest of her three daughters.

“There’s a hole in the earth without Bridgette Hempstead,” said Dee Scott. “And I feel it. And I feel like the world feels it. There’s definitely a void here on earth.”

Bridgette Hempstead was 35 when she felt something was amiss with one of her breasts. But a doctor refused to order a mammogram because she said young African-American women didn’t get breast cancer.

Hempstead got the test anyway.

“When she first got diagnosed 28 years ago,” said Scott, “and had she gone home and not did her mammogram, she could have been gone in two years. So, I literally could have been 16 years old without a mom.”

Soon, Hempstead formed the Cierra Sisters, a support group for black women living with breast cancer.

It turns out African-American women are still more likely than white women to die from the disease. So, Hempstead volunteered for any clinical trial she could, often teaming up with Dr. Gralow, a national leader in breast cancer research.

“Bridgette has over two dozen scientific publications in her name,” Dr. Gralow said. “That means she’s a real researcher. She’s been included in the research.”

And Hempstead’s patient advocacy has yielded tangible results.

“We have an implicit biased training out called ‘Just Ask,’” she said, “which means ‘let the patient decide. Don’t assume that you know or that you’re protecting them from research. Let them decide.’ Bridgette informed that whole piece of work.”

What drove her, her daughter was asked. “Faith, hope and endurance,” Scott said. “It’s the thing i talked about at her memorial service.”

Now Hempstead is gone. But many she could never know would live because she did.

“There are some people whose light shines so brightly that you cannot help but to see it and you cannot unsee it after you have seen it,” said Dr. Buckley. “That was Bridgette.”

Hers, a light that still shines.

©2025 Cox Media Group