Halfway through director Doug Liman's 1996 buddy comedy "Swingers," Mike (Jon Favreau) meets Nikki (Brooke Langton) while ordering a drink at a local dance bar. Fresh out of a six-year relationship, he makes awkward small talk with her, procures her number, and calls her later that night. When he gets Nikki's answering machine, it takes him a few tries to ask her out and leave his number. Soon, his intrusive, self-conscious thoughts sabotage his courtship. He redials numerous times and leaves multiple messages, explaining his relationship history before melting down and calling off his proposed date.

As he fumbles through his last message, Nikki jumps on the line: "Don't ever call me again."

During the 1990s, these kinds of brave encounters and voicemail meltdowns were some of the cringey and disjointed ways people attempted to find love. In the predigital age, meeting a romantic partner often required boldly approaching someone, initiating conversation, and exchanging phone numbers. If you were lucky, you could lean on friends, workplaces, and family members to facilitate a mutual connection. But anyone hoping for a relationship had to supply their own outward charm and rely on their own social circle.

While "Swingers" still holds up, that infamous voicemail scene has become a relic, a portal to a simpler (and sometimes more stressful) time. Since the rise of internet dating sites in the early 2000s and the proliferation of swipe-heavy dating apps over the last decade, it's become much easier to meet a potential romantic partner—and much more complicated too. These online services (from Match.com to Tinder, Bumble, and Hinge) connect users through algorithms based on personal profiles, questionnaires, and quick interactions that have expanded the pool of romantic possibilities and blurred the boundaries and definitions of relationships.

Their accessibility and universality have shaped how romantic relationships have formed over the last several years. According to a 2020 survey from the Pew Research Center, 29% of American adults said they'd used a dating app at one point in their life (an almost 20 percentage-point increase from 2013), while 12% said they married or have been in a committed relationship with someone they first met online. But the tide may be returning to more analog methods, as many daters (primarily from Generation Z) have recently begun to reject the apps, reverting to meeting romantic partners the old-fashioned way—at school, work, or through friends and family.

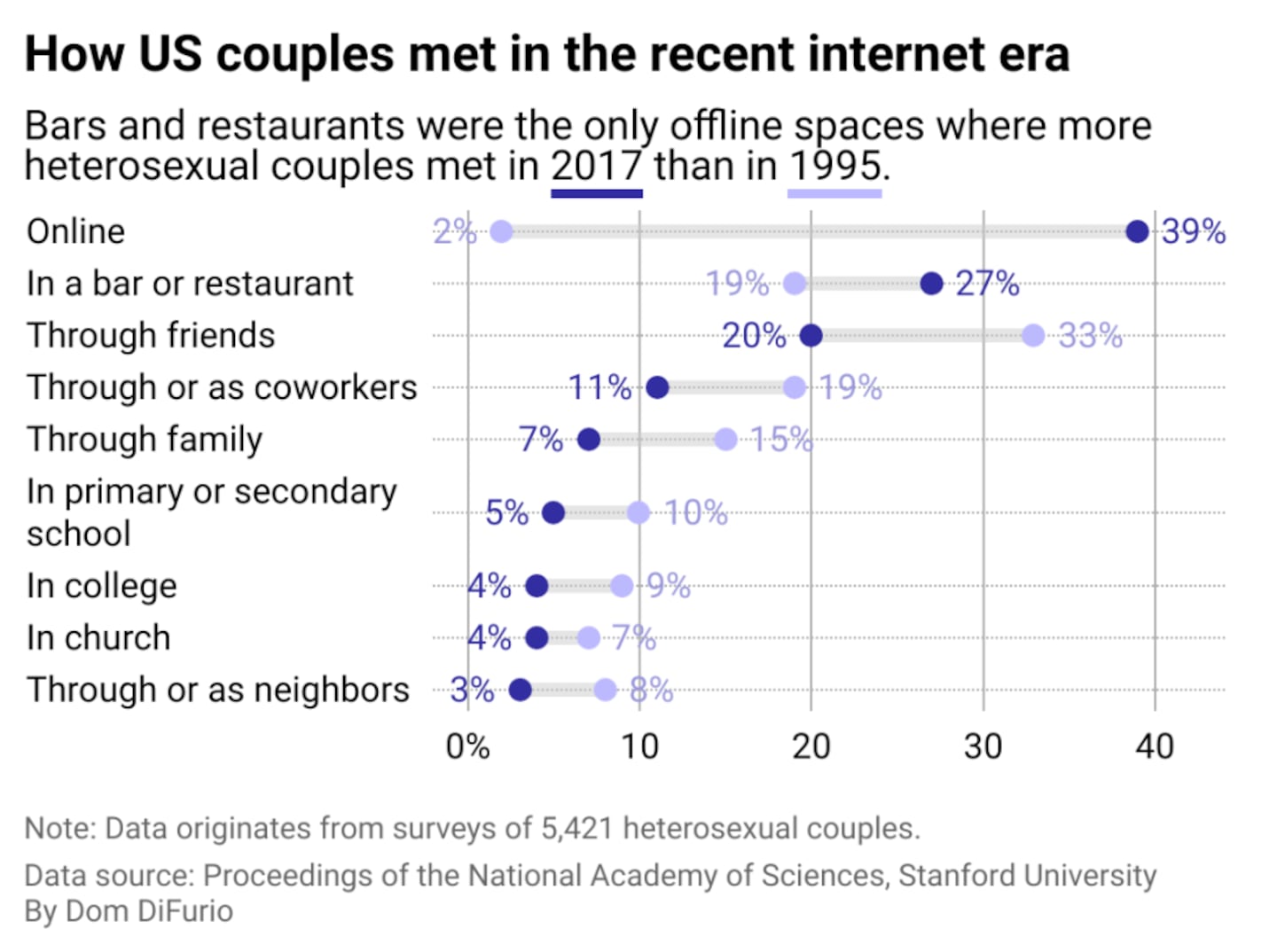

Spokeo visualized historical data from Stanford University researchers to illustrate the shifts in how couples have met and fallen in love over the years. The data studied only includes heterosexual couples and doesn't describe the dating habits of roughly 8% of the population that identifies as LGBTQ+, according to 2023 Gallup survey data.

Spokeo

Just 1 in 50 couples were sliding into each other's DMs in 1995

At the start of the millennium, attitudes toward online dating started to shift. Though Match.com arrived in 1995 and pioneered the online dating scene, the practice was originally "viewed as a refuge for the socially inept and as a faintly disrespectable way to meet other people," as Amy Harmon described in a 2003 New York Times article. Until 2013, heterosexual Americans were more likely to meet romantic partners through friends and trustworthy people who could vet and vouch for their potential romantic interests.

As more websites and services emerged on the internet (such as eHarmony, which built personality compatibility tests to match people in 2000), online dating grew in popularity. In the first half of 2003, more than 45 million Americans visited an online dating site (about 10 million more than at the end of 2002), according to Comscore Media Metrix. Meanwhile, online dating subscribers spent around $100 million per quarter (a $90 million increase from 2001), based on information from the Online Publishers Association (now Digital Content Next). The country's increased online presence dovetailed with the rise of Facebook and other social media platforms in the mid-2000s, instigating more social connections and destigmatizing how people began to meet.

Most of these online dating services (including OKCupid and Coffee Meets Bagel) were built on authenticity and vulnerability. They were intended for long-term commitments, thanks to their introspective questionnaires and psychology-based algorithms. That changed in 2009 with the emergence of Grindr (targeted toward gay and bisexual men and queer and transgender people) and then in 2012 with Tinder (catered to a younger, college demographic). These mobile apps allowed users to scan through photos and short bios of prospective singles. With a left or right swipe, users could chat with or pass on a prospect, creating an easier, faster, and more discrete dating process than what was required on traditional, profile-forward dating sites.

The growth of Tinder (in 2014, it processed about a billion swipes per day) led to various iterations of its swiping model; Hinge, for example, culled profiles through Facebook connections and friends of friends. That's how John, a 34-year-old New Yorker, met his long-term girlfriend a few years ago. After a "whirlwind" of dating over the previous years using Tinder and going on about 30 dates, he got "lucky" with one of his swipes. This new match "was the first person I had met that I thought could be something more," John told Stacker. "I was lucky, in that she had only started using Hinge, and I was the first ever online date she went on."

The pair met a little before Christmas, but John made sure to schedule a date ahead of the holiday. "I didn't want to risk the holidays passing and not meeting in person," he said. "Dating apps can be very hot and cold, and with so much abundance, if you don't meet up early, you're not taken seriously or you're just a 'pen pal.'" Though Hinge brands itself as the app "designed to be deleted," it's in its best interest to supply a wealth of choice and keep people like John swiping on the platform. As one frustrated swiper told CNN in 2023, "It's not just me who's being exhausted. It's the dating industrial complex trying to exhaust me."

Still, dating apps aren't the only social online hubs where people meet romantic partners. In 2015, Dave Strauss, a Northern Virginia native, met his girlfriend nine years ago while playing the online game Words with Friends. While he often commented with players in his area, he began having fuller online conversations with an opponent for about a month. Eventually, they decided to become Facebook friends, equally assuring they were real people. "Both single, local, and certainly interested in learning more about each other, I suggested we play Scrabble in person," Strauss, 56, told Stacker. "She liked the idea, but it ultimately morphed into a date that lasted hours."

The pair have been together ever since, but Strauss recognizes meeting online has its challenges. Though he had earlier relationships through dating apps (Tinder, Plenty of Fish) and more organic means, he feels the online apps are built more "to meet people and have fun" and that you shouldn't "expect to meet your 'one.'"

"Dating online opens up the universe to far more people than doing it organically," Strauss said. "However, because the people you meet are not in your social circles, it's a step removed from finding someone who is of a similar mindset."

Online dating is a more common way for people within LGBTQ+ communities to meet. According to a 2019 Pew survey, about half (48%) of lesbian, gay, or bisexual people aged 18 to 29 and just more than half (55%) of adults have used dating apps, and about 1 in 5 from both groups have either married or experienced a committed relationship with someone they met through a dating app. Another 2022 Pew survey found that although 3 in 5 (61%) lesbian, gay, and bisexual people said their online dating experience was positive overall, most people in this demographic who had used dating apps since the previous year reported feeling both excited (85%) and disappointed (84%) about the people they find while swiping.

Those mixed feelings track with the growing cultural rejection of the app-based dating model in recent years. Talk with enough people and you'll likely see millennials are growing tired of dating apps, while Gen Z singles are barely using them.

A 2023 Axios/Generation Lab survey showed that roughly 4 in 5 (79%) college and graduate students nationwide don't use any dating apps—even as little as once a month. Why? Well, for starters, more than half (56%) of Gen Z daters fear rejection or being cringe, according to Hinge's 2024 D.A.T.E. report. There's also the proliferation of "ghosting" (disappearing without communication) and the rise of "situationships" (ambiguous, undefined relationships), thanks to the abundance of choice.

"You can easily swipe through hundreds of people a day, and due to that, each swipe means very little," John said. "Guys end up swiping on everyone, whereas girls can be selective—but a match on their end could very easily be a guy just chain-swiping anyway." The algorithms aren't helping either, often hiding "super likes" and other premium features behind paywalls, and some daters—specifically in marginalized groups—can find harassment there too. The 2019 Pew survey found that about 3 in 5 female users aged 18 to 34 said someone on a dating site or app continued to contact them after saying they weren't interested. A similar percentage (57%) said they've been sent sexually explicit images and messages they never asked for.

As a result, younger people are reverting to how many people met before the digital era—through school, work, friends, and being out in the world. One common place is through running clubs, substituting the phone screen for a little exercise and socializing in large groups throughout major cities. But there are still digital tools that ditch the dating app model. Some users have created "Date Me" docs that can be linked in social media bios and share in-depth breakdowns of what someone is looking for in a romantic partner, along with calendar links and previous partner reviews. "If I were single now, I would try meet-up events in person," John said. "I wouldn't even touch an app anymore."

The dating apps are trying to keep up with this sentiment. Some are reinventing themselves and pivoting from the hookup model toward deeper connections, while others have aligned themselves with social causes that Gen Z users might care deeply about. Still, the oversaturation of technology has encouraged many young daters to reinterpret how they interact with the world, focus on self-care and authenticity, and find love in a way that makes them feel like real human beings again.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Additional editing by Elisa Huang. Copy editing by Paris Close.

This story originally appeared on Spokeo and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.