“Are you someplace where you can talk?”

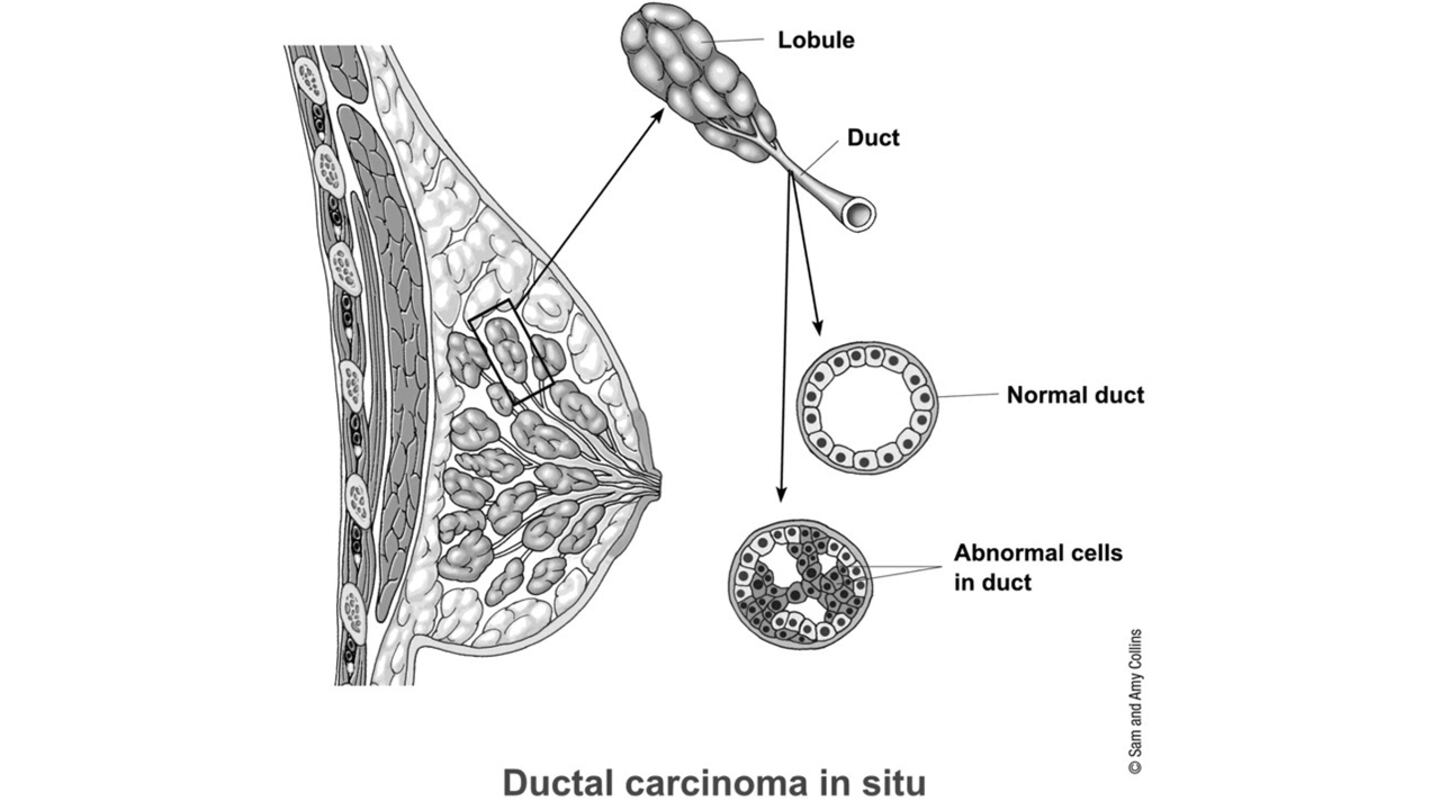

Those aren't words you want to hear from your doctor, especially when he's called to report the results of a biopsy. I scrambled to find a quiet corner and my head began to throb as I listened. Ductal carcinoma in situ. A very early variation of breast cancer. A pre-cancer really. Stage zero.

My rising panic was tempered by those two words. OK, I reasoned. This wasn’t so bad.

So, some three months later, I was stunned to find myself lying in the pre-op room of Atlanta’s Piedmont Hospital. IV lines were trailing out of my arms. My breast was marked up with Sharpie, a road map for the surgeon. I was awaiting a mastectomy.

Turns out that even though DCIS is so early it isn’t even officially “cancer,” it’s treated like one. Most doctors, including mine, don’t like to take chances. Be glad you caught it early, they say, and cut it out before it morphs into something more lethal.

But a new line of study is challenging that assumption.

What if instead of scheduling surgery, you watched and waited? A medical trial is looking at exactly that question. The results could revolutionize the way the medical community treats DCIS, which is being diagnosed in tens of thousands of women in the United States every year.

Active surveillance

The idea of active surveillance isn’t new. It’s already used by some men diagnosed with prostate cancer.

But when Dr. Shelley Hwang started talking about it with DCIS patients, she was greeted with alarm.

Hwang, who is now the chief of breast surgery at the Duke Cancer Institute, was alarmed herself. She saw women being treated aggressively for DCIS without good information. Does all DCIS morph into invasive breast cancer? How long does it take? Are there genetic or bio markers that could help predict progress?

“We just don’t have data,” Hwang said in an interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “We know what happens when we jump in right away (with surgery) and patients bear the side effects of that for the rest of their lives.”

Hwang said the combination of increased breast screening and better technology are creating a conundrum.

“We’re getting all of these new diagnoses before we really know what’s going to happen,” she said. “The question is what are we going to do with all that information?

"It creates tremendous anxiety and that leads to a lot of unnecessary procedures."

In 2017, Hwang launched a clinical trial aimed at trying to get answers. Called COMET, its goal is enroll 1,200 women with low-risk DCIS. Participants are randomly sorted into two groups. Some will undergo typical treatment, most likely surgery (either a lumpectomy or mastectomy), while others will be assigned to active surveillance.

Hwang said the biggest misconception about active surveillance is that the patient does nothing. Far from it, she said. They have regular screenings and, in some cases, endocrine therapy. It is a regimen of its own.

So far, Hwang has 260 women enrolled and is recruiting more. It will take four years to see results.

There is widespread interest in what she will find.

Dr. Len Lichtenfeld, interim chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society, said there is increasing recognition that doctors may be overtreating DCIS. But until they know more, that is seen by many as the safest route.

“The belief has taken hold among the public and medical professionals that we must treat this as a cancer,” he said. “Are we really being too aggressive?”

Surgery has serious side effects, like infection and scarring, he said. Reconstruction often requires multiple visits to the operating room. Afterward, many women report loss of feeling in their breasts, depression and anxiety.

“It’s time we do this study. It’s time we answer the question: Is what we’re doing helpful or hurtful?” he said.

‘I wanted to give myself time’

Wendy Stewart asked herself that question when she was diagnosed with DCIS in 2014. Almost immediately, her doctor urged her to get a mastectomy. She was confused. On the one hand, doctors were assuring her she had a low-grade form of a pre-cancer. On the other hand, they were pushing a drastic solution.

“I couldn’t understand why they wanted me to go through this extreme process, cutting my breast off,” she said.

So the Atlanta woman pressed pause.

“I wanted to give myself time to find out what was best for me,” she said.

She talked to more doctors and threw herself into researching DCIS. The more she learned, the more she realized that there was widespread confusion around the diagnosis.

Stewart eventually did have surgery, but it was on her own terms and her own timetable.

Three years after her diagnosis, she found a doctor in California who performed a procedure called extreme oncoplastic reduction, a breast conserving surgery. In that time period, the DCIS hadn’t grown, she said.

"Nothing had changed. Everything came back OK. There was nothing invasive," she said.

The 49-year-old IT professional said some questioned her decision not to take aggressive action right away. But she also found a surprising amount of support.

“For me, this was the best decision,” she said. “But it is also frightening to go through it alone wondering if you are doing the right thing.”

‘Women are doing it for each other’

As for me, I knew about Dr. Hwang’s work — thanks to Google — when I chose to undergo my own surgery in May 2016. But the clinical trial hadn’t started yet and, even if it had, I am not sure I would have been a candidate. My DCIS was intermediate grade and appeared to cover a large area. (The size was part of the reason I opted for a mastectomy instead of a lumpectomy.)

But even if I had been eligible, I’m not sure it would have been the right option for me. It would have made me anxious to know that there was even a possibility the DCIS had become invasive. It takes a certain mindset to be watch and wait. I am probably too much of a worrier.

Hwang acknowledges active surveillance isn’t for everyone.

>> Related: Breast cancer risk: Genetic makeup of tumor an indicator

“In this country, there is a history of action,” she said, explaining that in other parts of the world, less aggressive treatments are more acceptable. “We feel better if we are doing something.”

But Hwang wants women to have more than one option in their toolkit.

I am at peace with my decision. At the same time, if the results of the clinical trial were available, perhaps I could have made a different choice. One that didn’t involve four surgeries, weeks of physical therapy and some deep-rooted sadness that my body is, well, different than it once was.

Desiree Basila is a patient advocate for the COMET study, counseling women considering entering the trial. Like me, she had DCIS. She said she’s been struck by the attitudes of those signing on.

"Women are doing it for each other. They are doing it for their daughters. They are doing it for the woman in the waiting room who is scared to death. Because the women with DCIS, they have the answer," Basila said.

Cox Media Group