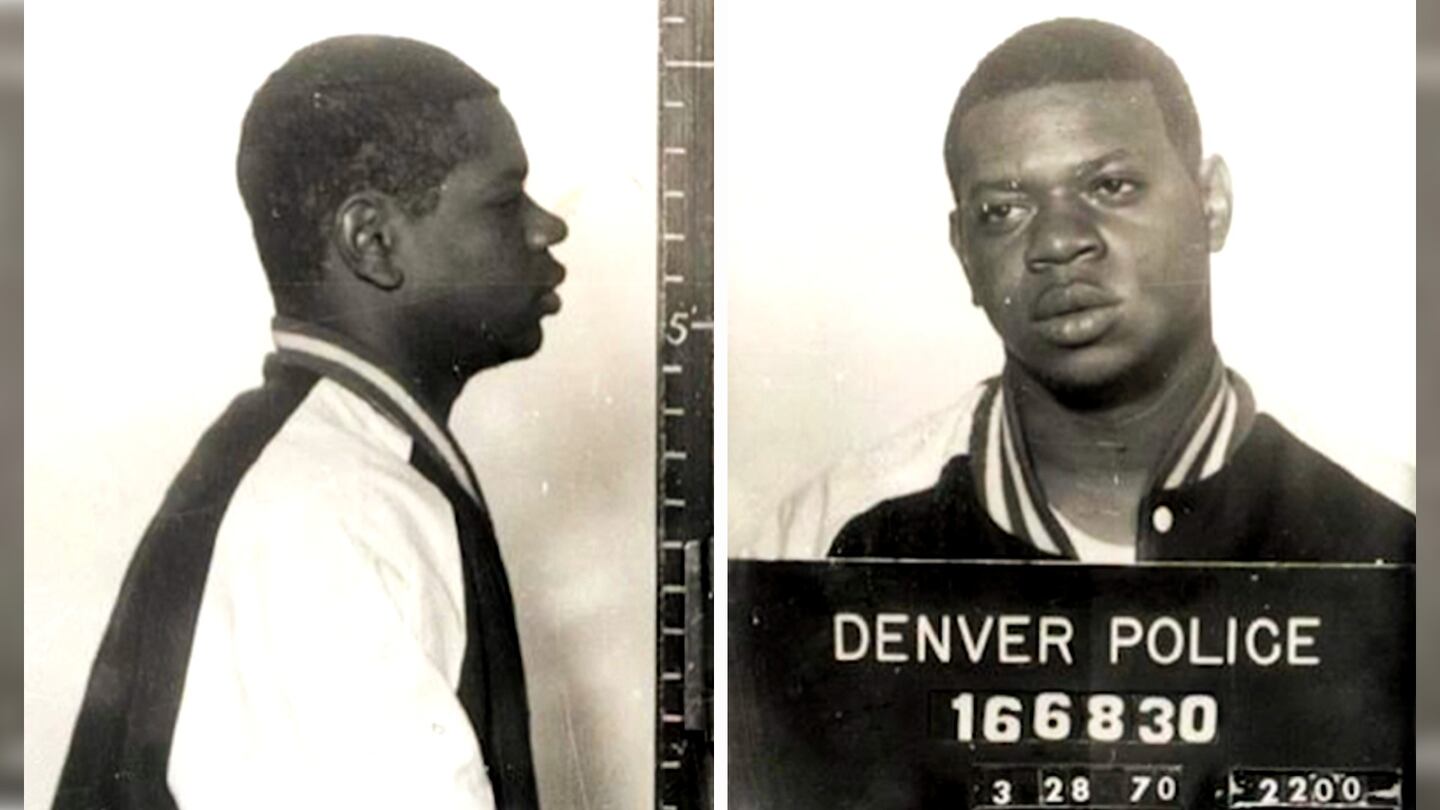

DENVER — A man who took his own life after killing a Colorado police officer nearly 40 years ago has been identified through DNA as a serial killer responsible for four additional murders between 1978 and 1981 in the Denver metro area.

Joseph Michael Ervin was 30 years old when he was accused of killing Aurora police Officer Debra Sue Corr, 26, with her own gun June 27, 1981. Corr, who had been on the force for a year, was Aurora’s first officer killed in the line of duty.

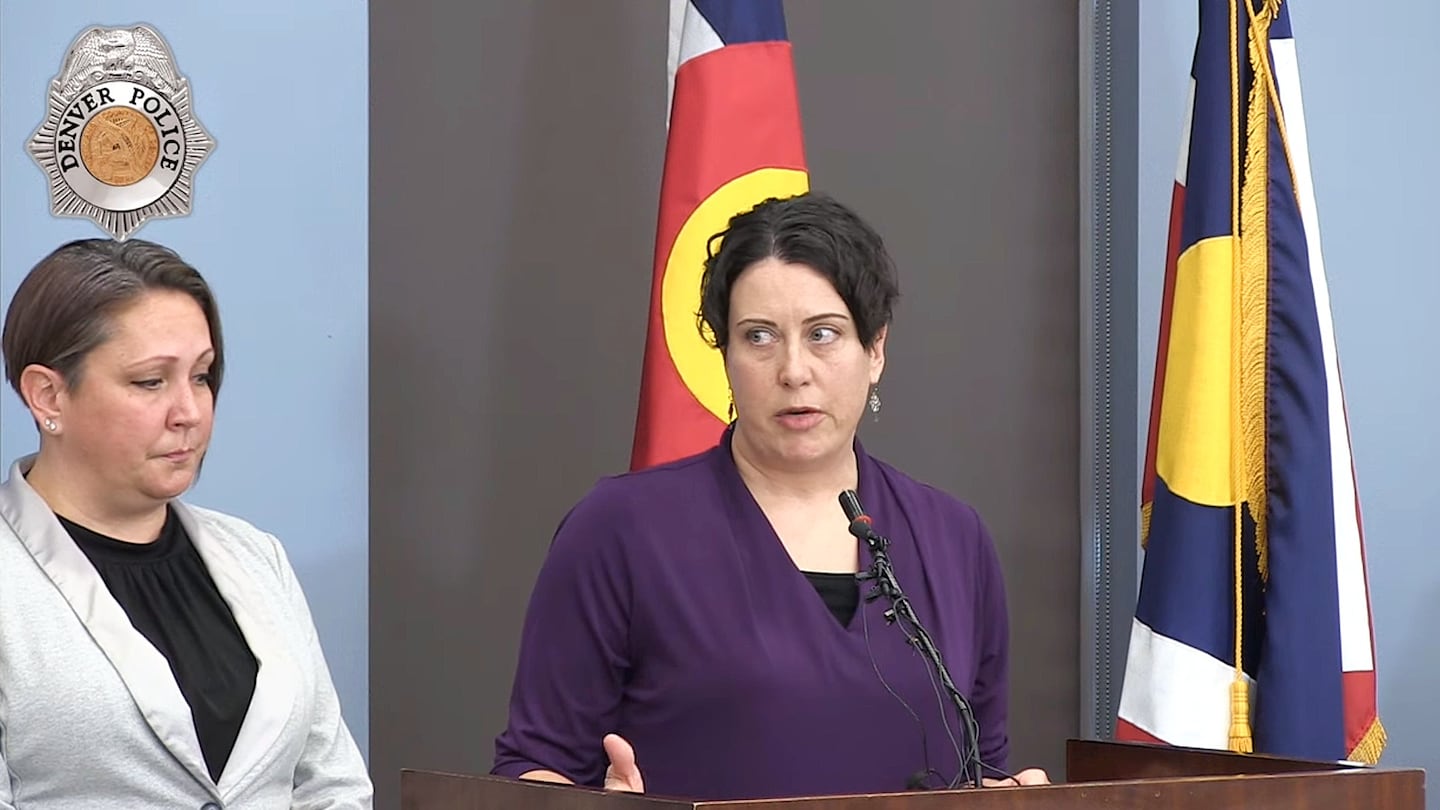

Denver police officials announced on Friday that Corr’s alleged killer, Joseph Michael Ervin, has been linked to the murders of three women and a pregnant teenager over a three-year span before Corr’s death. Ervin, 30, died by suicide in the Adams County Detention Center four days after Corr was killed.

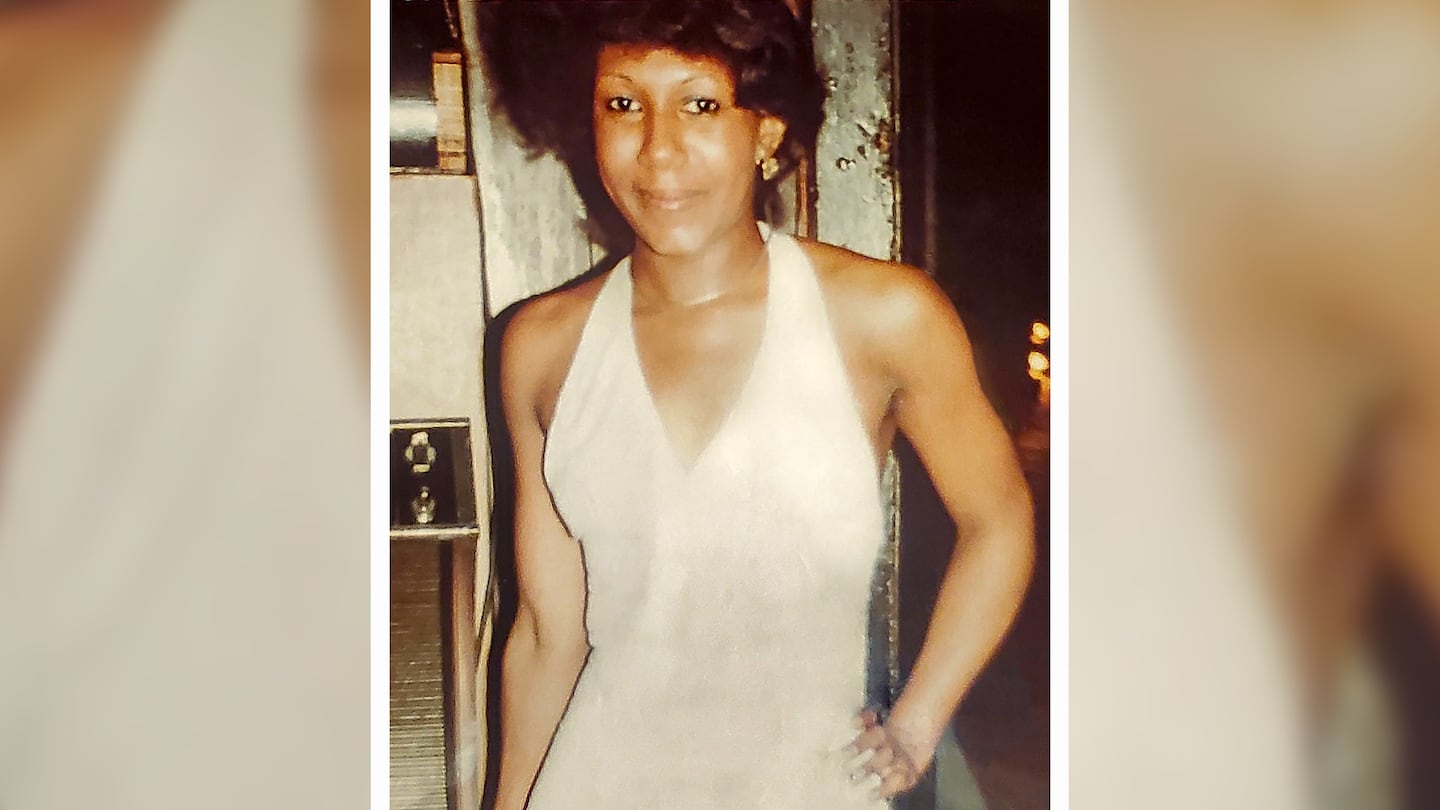

His additional victims have been identified as Madeleine Furey-Livaudais, 33, Dolores Barajas, 53, Gwendolyn Harris, 27, and Antoinette Parks, 17. All but Parks were killed within Denver city limits.

Parks, who was about six months pregnant, died just outside the limits in Adams County.

“While we recognize that identifying the suspect will not bring these ladies back, we hope it provides closure and healing for their loved ones and the Denver community,” Denver police Chief Paul Pazen said in a statement.

A string of brutal crimes

Ervin’s alleged crimes began around 6:15 p.m. Dec. 7, 1978, when he went to Furey-Livaudais’ home in the 1600 block of Poplar Street in Denver. When she answered her door, he forced his way inside.

Furey-Livaudais was stabbed to death, according to authorities.

The wife and mother was an author and ecologist who, at the time of her death, worked as an editor for the children’s magazine Ranger Rick, her daughters, Molly and Ariel Livaudais, said at Friday’s news conference.

In a voice shaking with emotion, Molly Livaudais described the promise their mother’s future held. That promise was abruptly destroyed the day she was killed.

“Tragically, we didn’t get to grow up with her and to hear her stories and witness the contributions she could have made to the world,” Molly Livaudais said.

Nearly two years after Furey-Livaudais’ death, on Aug. 10, 1980, Denver newcomer Barajas was walking to her job in the cafeteria of the Fairmont Hotel when she was accosted. Her body was found shortly after 7 a.m. at East 17th Avenue and Pearl Street, and, like Furey-Livaudais, she had been fatally stabbed.

Barajas, a married grandmother, was visiting family in Denver for the summer, according to police. The day she died was to be her last day working at the hotel before returning home.

“Ms. Barajas’ family still miss her very much and requested privacy as they process the emotions brought on by the closure of the case,” authorities said in a news release.

Four months later, on Dec. 20, 1980, Harris was at one of her favorite haunts, the Polo Club Lounge. It would be the last time anyone saw her alive.

Around 10:45 a.m. the next morning, she was found dead of multiple stab wounds near the intersection of East 47th Avenue and Andrews Drive, police officials said. According to CBS News, the street corner where Harris died was less than a block from where Ervin was living at the time.

Harris’ family said in a statement that she was a smart, soft-spoken woman who was always smiling. They said her murder was “devasting and unimaginable” to her loved ones.

“Gwen will forever be in our hearts and always our JOY,” her family said.

The killer next struck the following month just outside of Denver city limits, in Adams County. Parks, who had dropped out of Gateway High School in Aurora because of an unexpected pregnancy, was visiting her older boyfriend at his home hear 64th and Broadway on Jan. 24, 1981. According to the Denver Post, the pair had an argument and Parks stormed off.

Trash collectors found her body in a field, authorities said. She had been stabbed 23 times.

Her family told the Post in 2011 that her killer had thrust a stick inside of her, which they believed was intended to kill her unborn child.

Four months later, Corr stopped Ervin for a traffic violation at East Colfax Avenue and Moline Street in Aurora. As she was arresting him, Ervin broke free and in a struggle, he gained control of her service pistol.

He used it to kill the officer.

Aurora Police Explorer Scout Glen Spies, who happened to be passing by, saw Corr struggling with Ervin and stopped to help. The 19-year-old told CBS Denver last week that he pulled up behind Corr’s patrol car and got out of his own car, at which point he heard the officer screaming for help.

“I heard gunfire and tried to duck behind the patrol unit,” Spies told the news station. “He shot me and I fell to the ground.

“I heard him run to his car and take off. I tried to get up and move, but I couldn’t. I laid there in the middle of the street until help came. To me, it seemed like forever, but it was probably about two or three minutes.”

Listen to Glen Spies talk about the day he and Officer Debra Sue Corr were shot, courtesy of CBS Denver.

According to reports, Ervin was arrested at his home a short time later as he tried to saw Corr’s handcuffs off his wrist.

When the accused cop-killer took his own life, he also took his secret crimes to the grave with him — or so it seemed.

Identifying a killer

As it has in many cold cases solved in the past three years, the Denver-area cases were solved through genetic genealogy. Denver police Cmdr. Matt Clark said Friday that at the time of the murders, detectives used every tool at their disposal to investigate the crimes.

“They spent a tremendous amount of time on these investigations, following leads and questioning potential suspects,” Clark said. “Despite these efforts, the investigators were not able to determine the identity of the offender in these cases.”

All leads were exhausted and each of the cases, which at that point were investigated as separate incidents, went cold. DNA analysis was a few years off when the victims were slain, but in the intervening years, detectives sought help from the burgeoning technology.

Watch Friday’s news conference below.

In 2004, outside funding helped establish the department’s cold case unit, members of which have reviewed each case multiple times. In 2013, cold case detectives were able to use the killer’s genetic profile to tie the murders of Furey-Livaudais and Barajas to the same unknown killer.

“This new evidence created significant momentum for the investigative team that soon snowballed,” Clark said.

In 2015, the killer’s DNA linked Harris’ murder to the other two cases.

According to the Adams County Sheriff’s Office, a detective reviewed Parks’ case in 2009 and sent about 20 items of evidence to be tested for DNA. Two years later, in 2011, the items were once again examined but many of the sources of DNA had been used up in prior testing.

“(DNA technical leader Rosalind Ekx) swabbed an empty glass tube that previously contained evidence obtained from the victim, hoping to collect trace residue that contained DNA,” Adams County authorities said. “Rosalind performed analysis on the new collection and was able to obtain a DNA profile of an unknown male.”

The profile was uploaded into the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS, and, in October 2018, it was matched to the profile of the killer in Denver’s three cases.

Still, the source of the DNA remained unknown.

According to police, that began to change in 2019, when the Denver Police Department’s crime lab began conducting in-house genetic genealogy. They got a hit on a possible relative of the killer in Texas.

A familial search conducted last summer identified a close relative of the unknown killer, who investigators subsequently identified as Ervin. His remains were exhumed from an Arlington cemetery late last year, Clark said.

Analysis of DNA taken from his remains confirmed the match earlier this month.

“I appreciate the patience and resilience of the families and the community over the past 40 years as these cases remained unsolved,” the commander said. “These women were not forgotten.”

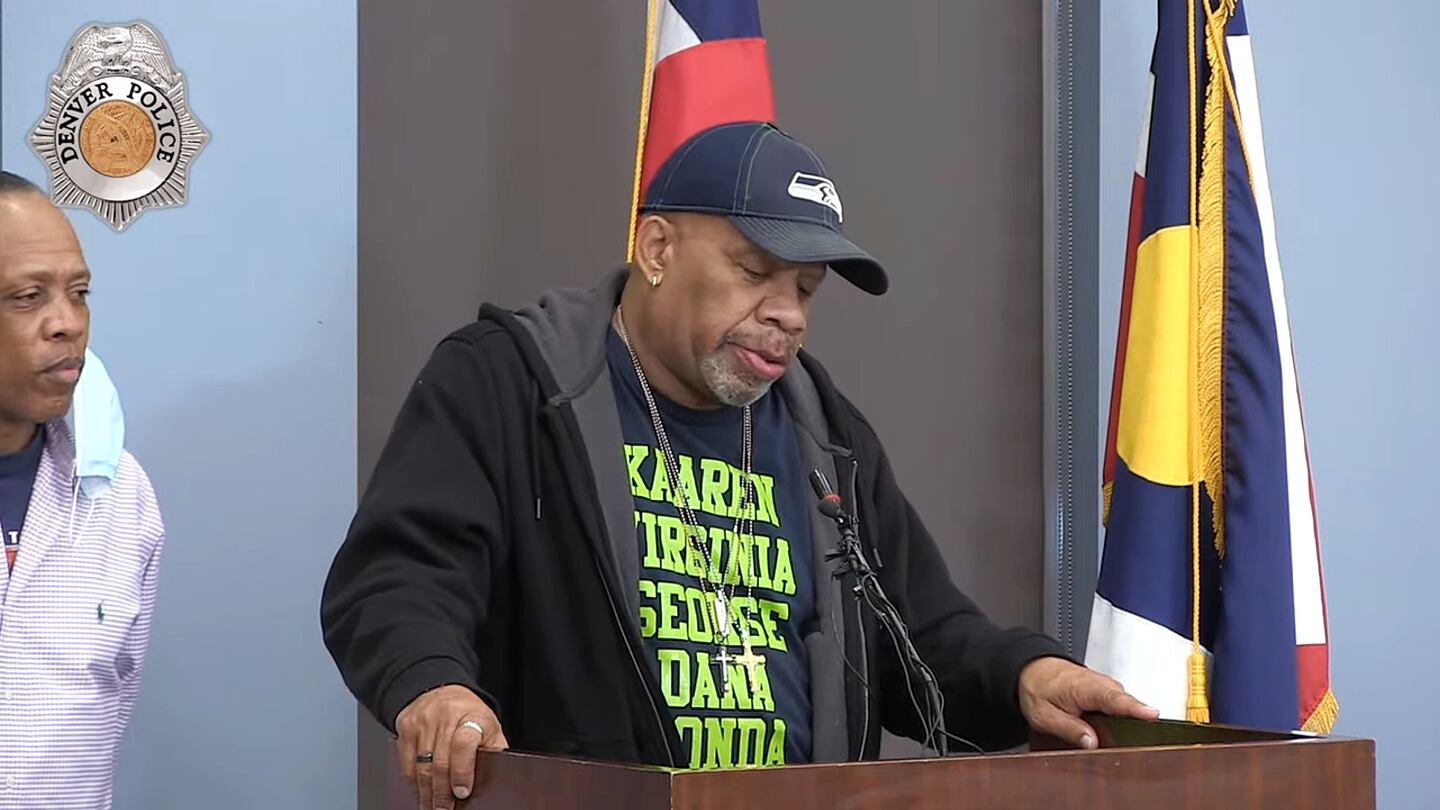

Standing with Furey-Livaudais’ daughters at Friday’s news conference were Parks’ two brothers, George and Karl Journey.

“This has taken a long time,” George Journey said. “We can finally have peace knowing who did this to my little sister.”

Parks was the youngest of seven children. Her sisters, who washed her body and applied her makeup before her funeral, have since died, leaving her two brothers as her only remaining siblings.

“I wish my sisters and my mom could be here to see this,” Journey said. “Unfortunately they didn’t live long enough to see this, but I know they are here with us in spirit.”

>> Read more true crime stories

Karl Journey said he knows his mother and sisters are “sitting high and looking low” on those at the news conference and thanking cold case investigators for their hard work.

“Anybody who had anything to do with this, believe me, they’re saying, ‘Thank you and God bless you,’” he said.

“I’m angered because he didn’t face justice,” George Journey later told CBS Denver. “But I know my mom and family wouldn’t want us angry. They’d want us to be happy that this is all brought to a close.”

Molly Livaudais talked about the enormity of the announcement and finding out that her mother’s killer was responsible for so many other brutal slayings.

“It’s been a lot of information to absorb so suddenly after all this time,” she said, taking a deep breath.

Livaudais said learning about Corr’s line-of-duty death was “personally, very impactful.” She credited Corr with unknowingly stopping a serial killer from claiming more victims.

“She was out doing her job when she attempted to arrest this serial killer for an unrelated crime,” Livaudais said. “In the course of his arrest, she was murdered herself.

“With her sacrifice, she prevented him from killing anyone else, and it’s clear that he wasn’t going to stop on his own.”

©2022 Cox Media Group