SOMERTON PARK, Australia — Australian authorities are looking into claims that genetic genealogists have identified the man at the center of one of the the country’s most enduring mysteries.

The University of Adelaide, along with genealogists from Identifinders International, announced last week that they have identified the “Somerton Man,” a mystery man found dead on Somerton Beach in 1948, as Carl “Charles” Webb.

Webb was 43 when he was found by beachgoers. According to the researchers, he was born to Richard August Webb and Eliza Amelia Morris Grace in Footscray, Victoria, in 1905.

Webb lived and worked in Melbourne at the time of his death. He was an electrical engineer and instrument maker.

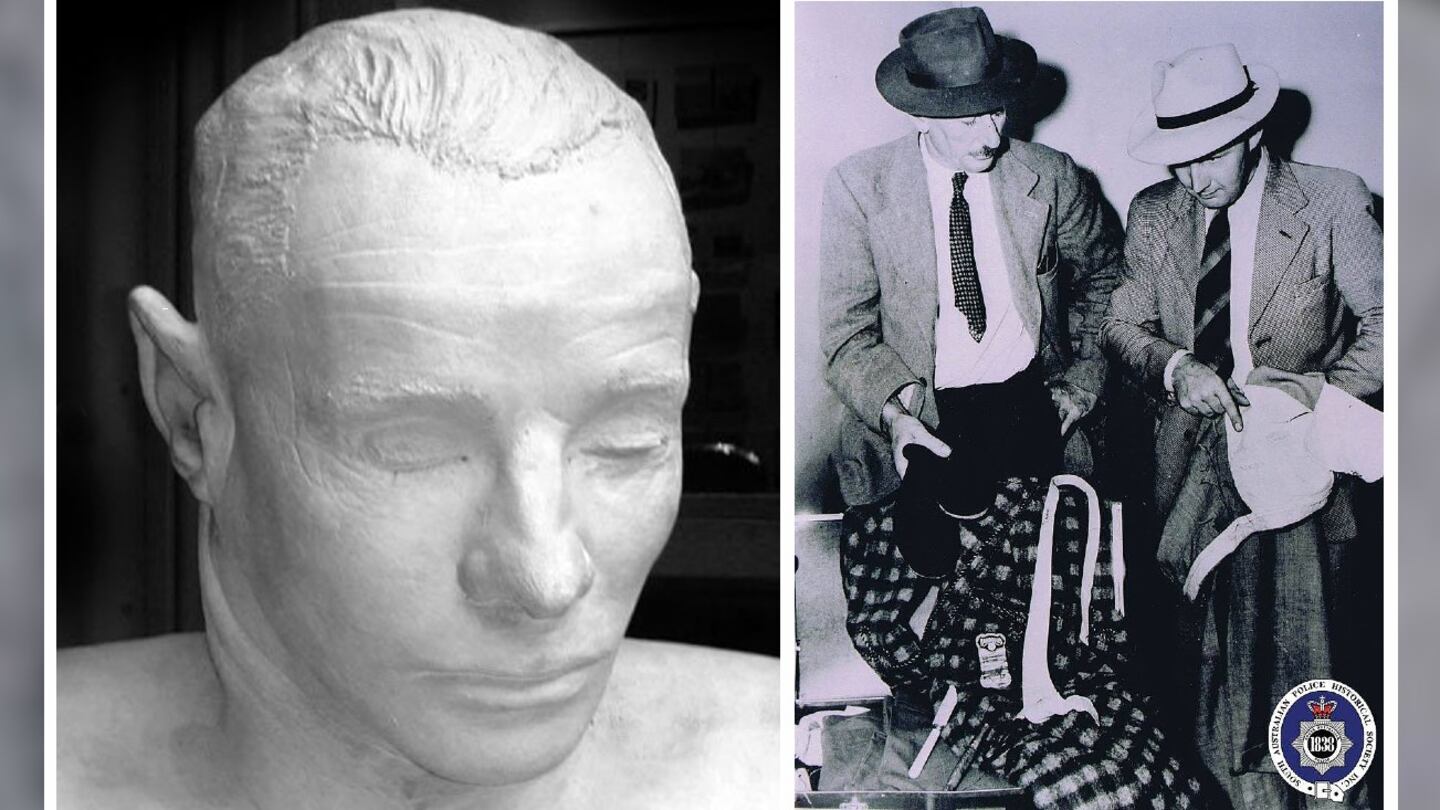

“The identification was made based on DNA obtained from hair found embedded in the man’s plaster death mask, held at the South Australia Police Museum,” the investigative team said in a news release. “Professor Derek Abbott of the University of Australia was permitted access to the mask and the hair in 2011 by the South Australia Police.”

Abbott and Colleen Fitzpatrick, a renowned genealogist who founded Identifinders International, used new DNA technology that allows more thorough testing of rootless hair to obtain the unknown man’s genetic profile. They then used that profile to build the man’s family tree and narrow down his possible identity.

In March, after months of painstaking work, their search heated up.

“In all this soup and ocean of DNA cousins, we were able to connect one of them to Carl’s father and one of them to Carl’s mother,” Fitzpatrick told The New York Times. “You really kind of narrow it down so much it could be any one of Carl’s siblings — but Carl is the one with no documented death.”

Happy to announce @CFitzp of @Identifinders assisted with solving the #SomertonMan. pic.twitter.com/5B0WDwEMgW

— Identifinders International, LLC (@Identifinders) July 27, 2022

Police and Forensic Science South Australia have not yet been able to confirm the findings by Abbott and the genealogists. South Australia Police officials, at the urging of Abbott, exhumed the long-unknown man’s remains last year to obtain his DNA, and they are awaiting the results of those tests.

“South Australia Police are still actively investigating the ‘Somerton Man’ coronial matter,” a police spokesperson said Wednesday. “We are heartened of the recent development in that case and are cautiously optimistic that this may provide a breakthrough.

“We look forward to the outcome of further DNA work to confirm the identification, which will ultimately be determined by the coroner.”

A tragic discovery

Beachgoers on horseback in Somerton Park stumbled upon a body the morning of Dec. 1, 1948. The man, who was estimated to be in his 40s, was found lying with his head resting against a seawall on Somerton Beach, just across the street from a home for handicapped children.

The man carried no identification, and though he was fully clothed in a jacket and tie, the tags on all his clothing had been ripped out. In his pockets were cigarettes, matches, Juicy Fruit gum and unused train and bus tickets.

A partially smoked cigarette lay on his jacket lapel.

Several witnesses reported seeing the man the evening before he died, including some who saw him before he was spotted on the beach. Those who saw him lying in the sand, propped against the seawall, thought he had dozed off.

The man had no visible injuries and appeared physically fit. Because of the way his body was positioned, with his legs out in front of him and his feet crossed, authorities surmised that he had died in his sleep.

The man’s autopsy, detailed in reports from the 1949 coroner’s inquest, found extensive congestion in his organs, as well as bleeding in his stomach and liver. The theory was that the man had been poisoned, either by his own hand or by someone else’s.

Testing for all known “common poisons” found nothing, however, and authorities could not definitively determine how he died.

They also were unable to determine his identity, and 10 days after his death, his body was embalmed. The Advertiser in Adelaide reported at the time that it was a first for the police agency.

An ‘unparalleled mystery’

More than six weeks later, on Jan. 14, 1949, staff members at the Adelaide train station discovered a suitcase the unidentified man had checked in the night before he died. Inside the luggage were several articles of clothing, including a tie and other items bearing variations of the name “T. Keane.”

Detectives could find no one by that name missing in any English-speaking country, authorities said.

“Police believe that whoever removed the name tabs from the clothing either overlooked the names on the two pieces of clothing or purposely left them on, knowing that the dead man’s name was not ‘Keane’ or ‘Kean,’” the Advertiser reported at the time.

According to the newspaper, they linked the suitcase to the dead man after finding a bundle of thread identical to that used to mend the pocket of his trousers. The case also held a small button identical to the buttons on the man’s pants.

By April 1949, authorities were calling the case an “unparalleled mystery” that had extended to inquiries with authorities in multiple other countries, including the FBI and Scotland Yard.

At the June 1949 inquest, the coroner determined that the bottoms of the man’s shoes were clean, possibly too clean for a man who had been walking as much as the dead man. There were also no signs of vomiting or seizure activity at the beach crime scene, despite the belief the man had been poisoned.

Some investigators theorized that the man had died elsewhere and had been carried onto the beach and left there to be found.

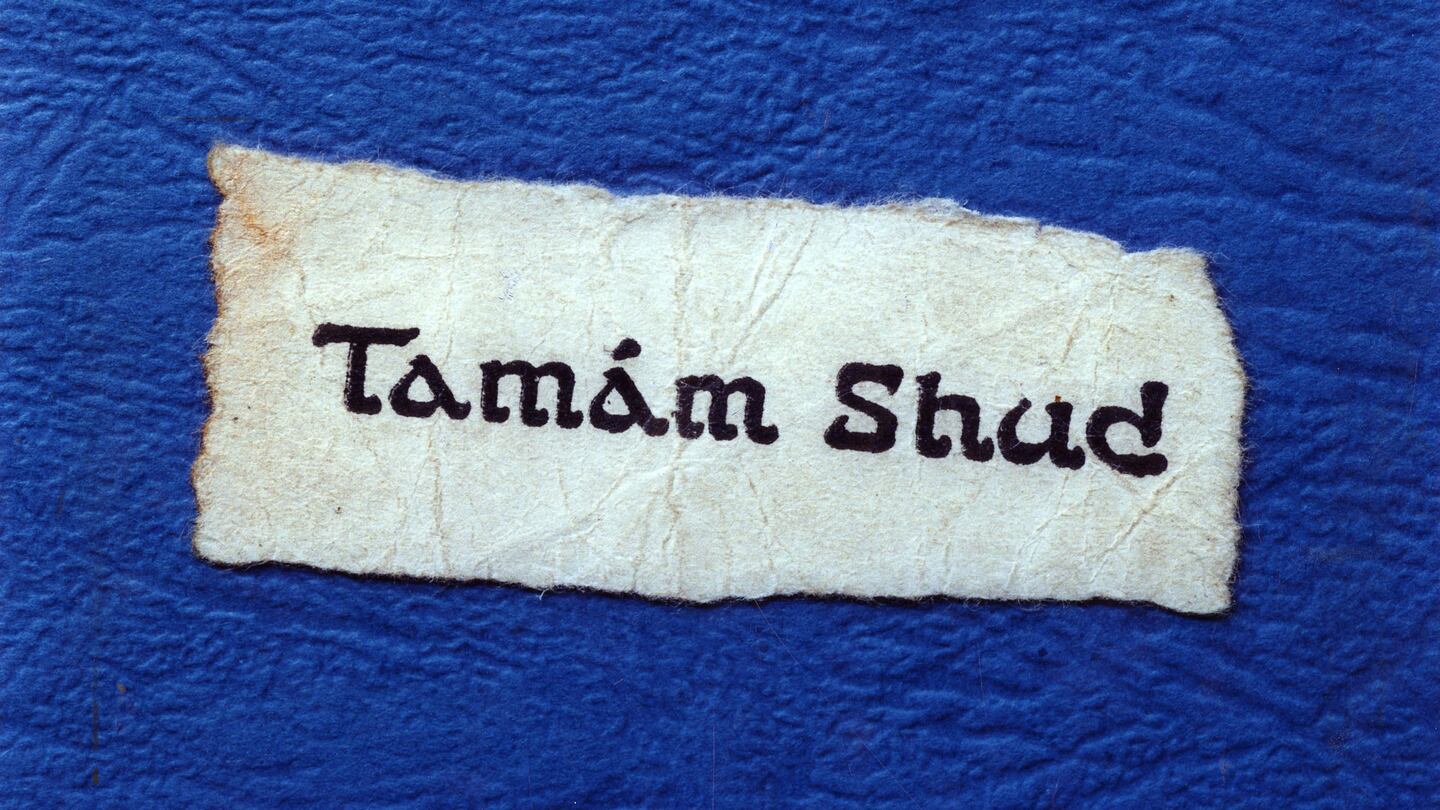

Around the time of the inquest, the coroner reexamined the man’s clothing and found a previously unnoticed fob pocket inside one of the man’s pants pockets. Inside was perhaps the biggest mystery of the Somerton Man: a rolled-up piece of paper bearing the words “Tamám Shud.”

The Persian phrase, which was found on the last page of Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, means “the end” or, “It is finished.”

The theme of the poems was the need to live life to the fullest and have no regrets when that life is over. The man’s lack of identification, along with the scrap of paper, led some investigators to lean toward the suicide theory.

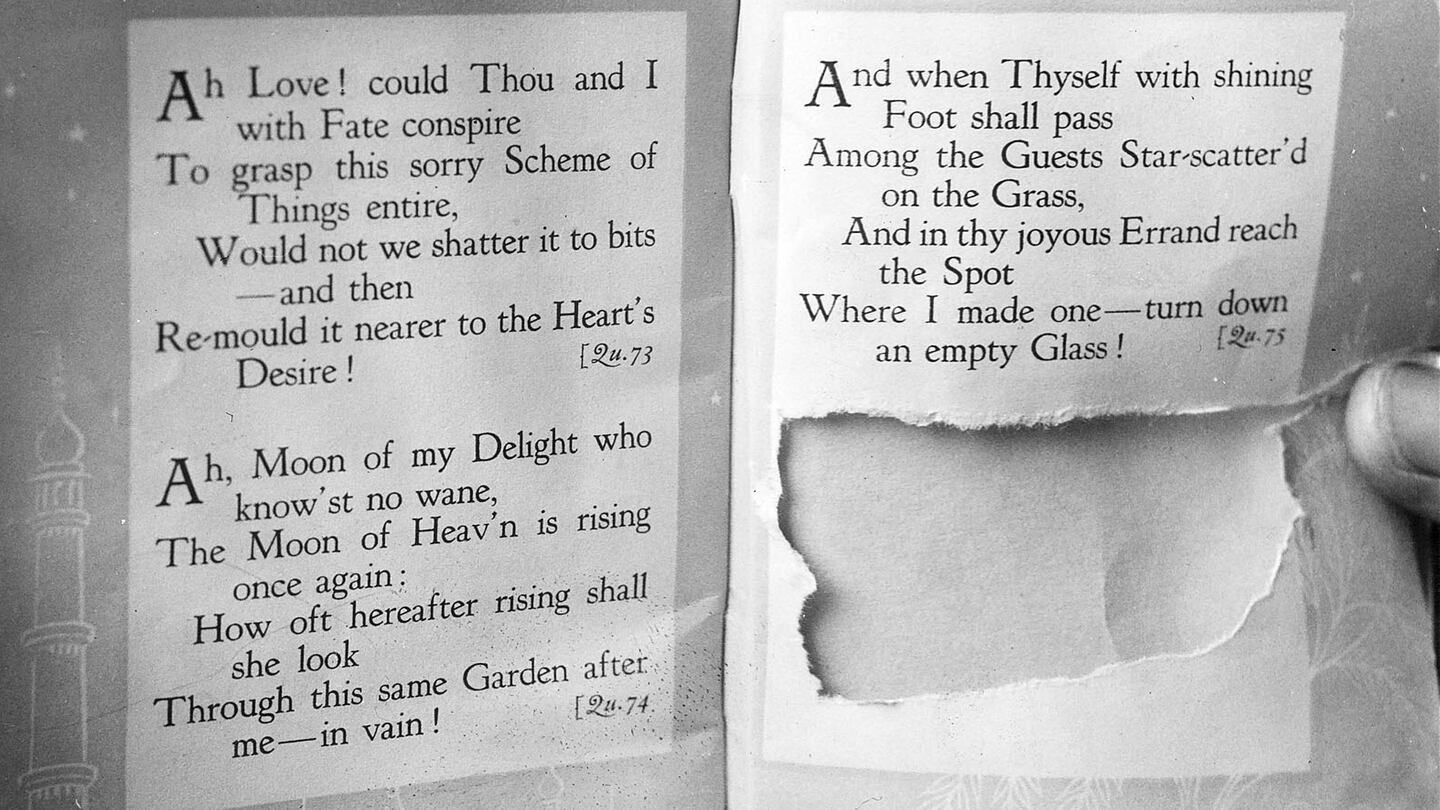

The poetry book from which the phrase had been torn was later turned in to police by a man who said he found it in his car but did not know how it got in there. He said he believed it had been tossed into his back seat as the car was parked near the spot where the Somerton Man had been found.

The book had a handwritten sequence of letters on the back cover, which prompted speculation that it was some sort of code. It also contained a couple of phone numbers, including the number of a woman who lived near the beach where the man was found.

The woman, a nurse named Jessie Thomson, denied knowing the unidentified man.

False identifications and theories on the man’s death proliferated over the years, though none of them panned out. According to the Times, some armchair sleuths theorized that the man was a spy or involved in postwar smuggling due to the removal of all hints of his identity.

By 2011, Abbott had already spent years looking into the unsolved case. That year, however, authorities allowed him to take 50 hairs from the Somerton Man’s death mask, which had been obtained before his burial.

Some of the man’s DNA was pulled from the hair, which was missing its root bulbs, in 2012 and 2018. Meanwhile, in 2021, authorities exhumed the Somerton Man’s body to get additional DNA samples from the remains.

In February, as the newest DNA technology gained traction, Abbott and Fitzgerald were able to pull enough of a profile to perform genetic genealogical research.

“By filling out this tree, we managed to find a first cousin three times removed on his mother’s side,” Abbott told CNN last week.

On July 23, they got a match between the Somerton Man’s DNA and the DNA of Webb’s distant relatives.

“It’s like one of these folklore mysteries that everybody wants to solve, and we did it,” Fitzpatrick said. “It just felt like I climbed — and I was at the top of — Mount Everest.”

Watch South Australia authorities discuss the exhumation below.

Many questions remain about Webb’s death. Even more remain about his life.

Fitzpatrick said the last record the team found for Webb was in April 1947 when he left his wife, Dorothy Robertson. She was also known as Doff Webb.

“He disappeared, and she appeared in court, saying that he had disappeared and she wanted to divorce,” Fitzpatrick told CNN.

By 1951, Robertson had moved to Bute, South Australia, about 90 miles from Adelaide. The researchers have theorized that Webb might have traveled to Adelaide in December 1948 to find his wife.

“It’s possible that he came to this state to try and find her,” Abbott said. “This is just us drawing the dots. We can’t say for certain that this is the reason he came, but it seems logical.”

>> Read more true crime stories

Abbott and Fitzgerald have been able to explain some details of the case. While conducting their research, they learned that Webb had a brother-in-law.

The man’s name was Thomas Keane, which matched the name on the clothing found in Webb’s abandoned suitcase. Webb’s love of poetry could also explain why he carried a slip of paper torn from a poetry book when he died, according to The Washington Post.

The newspaper reported that any relatives who remembered Webb are long gone. His living relatives have no insight into his life, and they have no photos to share of the man who has remained a mystery for more than seven decades.

Abbott hasn’t lost hope.

“I’m hoping, as his name gets out there, there will be somebody that will have an old photo album in a garden shed somewhere,” the professor said.

©2022 Cox Media Group