AURORA, Colo. — An independent probe into the death of Elijah McClain, who died following a 2019 encounter with Colorado police, has found that Aurora officers and fire medics erred in stopping the young Black man, using a carotid chokehold on him and administering a lethal dose of ketamine.

McClain, 23, was walking home from purchasing iced tea for his cousin the night of Aug. 24, 2019, when officers responded to a report of a “sketchy” man walking in the neighborhood.

Just 18 minutes after first being stopped, McClain was dying.

This young man’s name is #ElijahMcClain, & animal welfare friends, he was one of us. He spent his lunch breaks at his local animal shelter playing music because he felt it was soothing to the animals. His family deserves an independent investigation. #ElijahMcClainWasMurdered pic.twitter.com/nFWVCg25m8

— Marc Peralta (@_MarcPeralta) June 26, 2020

A grand jury in Colorado will review the death of Elijah McClain, the 23-year-old Black man murdered by Aurora police in August 2019. The investigation comes as part of an independent investigation, following nationwide protests over the police killings of Black Americans. pic.twitter.com/Fpig9apXx3

— Grande Capo (@VoLinxx) January 9, 2021

A scathing, 157-page investigative report, which was commissioned by the city of Aurora, found that Aurora police Officer Nathan Woodyard had little, if any, reason to stop McClain that night. It faulted the officers for their use of force, as well as city fire medics, who believed officers’ claim that McClain was suffering from “excited delirium” and administered ketamine, a powerful sedative, to calm him down.

The medics never actually examined McClain before administering a dose fit for a man much larger than the 5-foot-7, 140-pound McClain, who subsequently went into cardiac arrest.

He died Aug. 30, 2019, after being removed from life support.

The panel, which consisted of a law enforcement expert, a legal expert and a medical expert, also called into question the thoroughness of the Aurora Police Department’s own investigation into McClain’s death, which was conducted by detectives in the department’s Major Crime Division.

The case was never turned over to Internal Affairs investigators, the panel wrote.

They found that Major Crime’s investigation revealed “significant weaknesses” in the department’s accountability systems.

“The interviews conducted by Major Crime investigators failed to ask basic, critical questions about the justification for the use of force necessary for any prosecutor to make a determination about whether the use of force was legally justified,” Monday’s report states. “Instead, the questions frequently appeared designed to elicit specific exonerating ‘magic language’ found in court rulings. Major Crime’s report was presented to the District Attorney for Colorado’s 17th Judicial District and relied on by the Force Review Board, but it failed to present a neutral, objective version of the facts and seemingly ignored contrary evidence.”

>> Related story: Colorado governor orders new probe of Black man’s 2019 death in police custody

District Attorney Dave Young’s review of the case also failed to assess the officers’ conduct and “did not reflect the rigor” one would expect when assessing whether or not a crime has been committed, according to the report. Young did not find sufficient evidence to press criminal charges against the officers or medics.

The report points out, however, that Young failed to consider Colorado’s requirement that officers have “reasonable suspicion” of a previous or pending crime in order to stop a person. Aurora officers relied solely on McClain’s location in a “high crime area” and his winter attire on a summer night as cause for the stop.

“Neither the neighborhood nor the ski mask by themselves or together are sufficient to create reasonable suspicion without more,” the panel found.

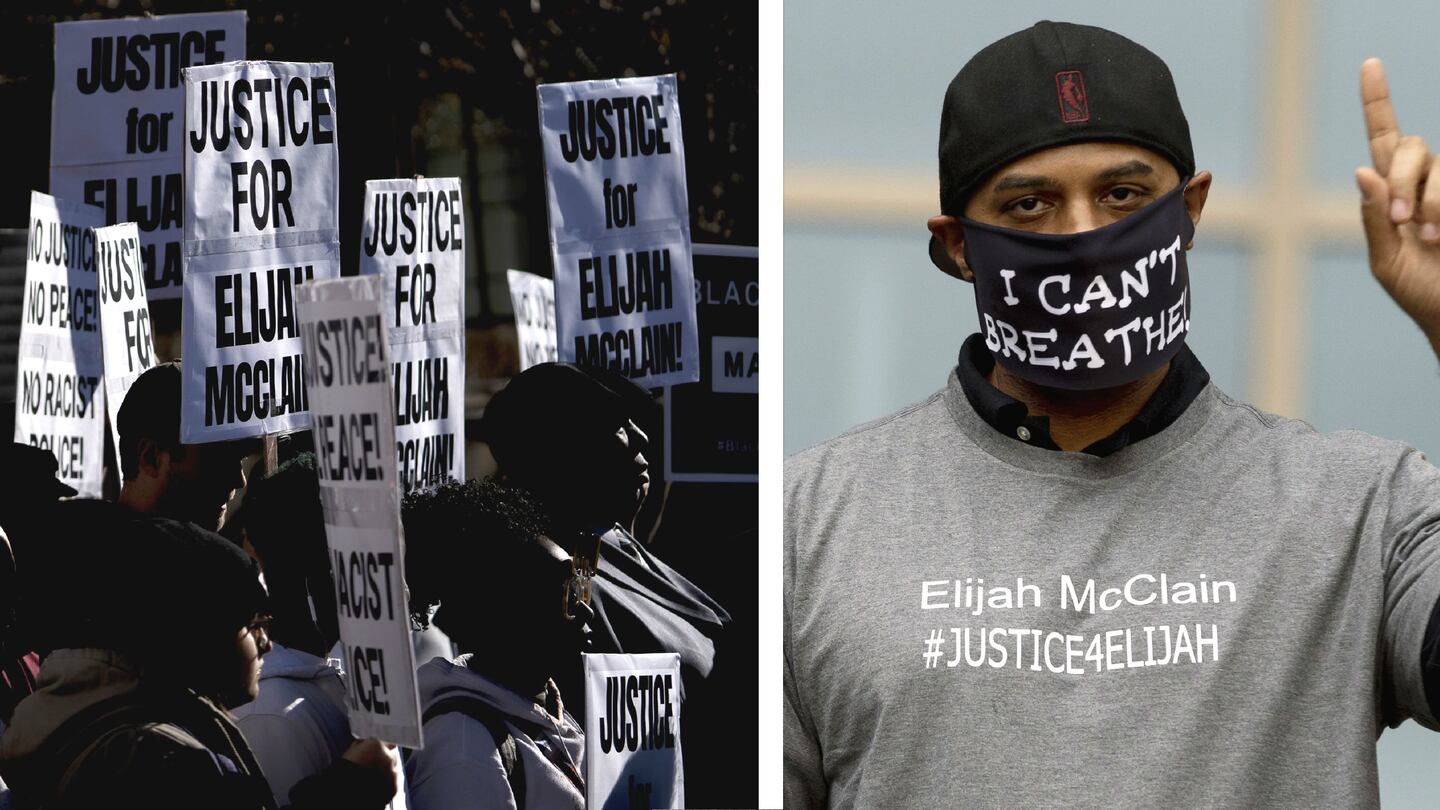

McClain’s death was reexamined in the wake of the May 25, 2020, death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers. Four former officers are awaiting trial on charges including murder.

Like Floyd, some of McClain’s last words were, “I can’t breathe.” The phrase has become a rallying cry for demonstrators, including the nationwide Black Lives Matter movement, demanding changes in policing.

The independent panel found that it had insufficient information to determine if “implicit bias” against people of color played a role in police officers’ and medics’ encounter with McClain. It did urge the city to assess its efforts to ensure that bias, either implicit or otherwise, does not affect encounters with the public.

“Research indicates that factors such as increased perception of threat, perception of extraordinary strength, perception of higher pain tolerance and misperception of age and size can be indicators of bias,” the panel wrote.

The evidence detailed in the panel’s report indicates that each of those factors did come into play in McClain’s case.

Mari Newman, an attorney representing McClain’s father, told NBC News on Monday that the independent report supports all of the allegations her clients have made regarding the way McClain was treated before he died.

“This is a broadside on the city of Aurora from top to bottom, beginning with the illegal stop that set the wheels in motion and the illegal conduct every step of the way,” Newman said.

Lawyers representing McClain’s mother, Sheneen McClain, agreed.

“Elijah committed no crime on the day of his death, but those who are responsible for Elijah’s death certainly did,” they said in a statement obtained by The Associated Press.

>> Related story: Elijah McClain’s police custody death gets grand jury investigation

Aurora Police Department officials declined comment Monday, NBC News reported. Fire Rescue officials could not be reached for comment.

The Colorado Attorney General’s Office also investigated McClain’s death, at the orders of Gov. Jared Polis, to determine if criminal charges are warranted. Last month, Attorney General Phil Weiser announced that the case was being sent to a grand jury.

The U.S. Department of Justice and the FBI are also reviewing the case for potential federal civil rights charges, the AP reported.

The stop

A passerby called the Aurora Police Department’s 911 dispatch at 10:29 p.m. on Aug. 24 to report a man in a black ski mask walking down Billings Street in Aurora, located about 10 miles from downtown Denver. The caller said the man was walking and waving his arms, and he told the dispatcher the man “might be a good person or a bad person.”

Listen to the 911 call below.

McClain was walking toward a convenience store, listening to music through his earbuds.

In the recording of the call, the man tells the dispatcher that no weapon was involved and that neither he nor anyone with him was in danger.

Thirteen minutes after the call, Woodyard arrived and spotted McClain, who by that time had left the store and was walking back home along Billings. The officer’s body-worn camera footage showed that McClain had his cellphone in one hand and a plastic bag in the other, according to the investigative report.

Woodyard got out of his patrol car and ordered McClain to stop.

“Within 10 seconds of exiting his patrol car, Officer Woodyard placed his hands on Mr. McClain,” the report states. “Mr. McClain had no observable weapon and had not displayed violent or threatening behavior. No crime had been reported.”

“Hey, stop right there. Stop,” Woodyard tells McClain in body camera footage.

According to the footage and police reports, McClain says he had a right to go where he is going.

“I have a right to stop you because you’re being suspicious,” the officer tells him.

The panel investigating the stop said that an officer, when conducting an investigatory stop known as a Terry stop, must have “reasonable objective grounds” and an “articulable” or “reasonable suspicion of criminal activity” in order to justify the stop.

The Terry stop must also rely on “the least intrusive means reasonably available to verify or dispel the officer’s suspicion in a short period of time.”

In interviews with Major Crime investigators, Woodyard and the other officers were unable to articulate the crime they thought McClain had committed or was about to commit, the panel found.

“Upon review of the evidence available to the panel, Officer Woodyard’s decision to turn what may have been a consensual encounter with Mr. McClain into an investigatory stop — in fewer than 10 seconds — did not appear to be supported by any officer’s reasonable suspicion that Mr. McClain was engaged in criminal activity,” the report states. “This decision had ramifications for the rest of the encounter.”

The frisk

The officers then frisked McClain, who protested and begged to be left alone.

“I am an introvert. Please respect the boundaries that I am speaking,” he tells the officers in the footage.

The officers tell McClain to relax, at which point he tells them, “I’m going home. Leave me alone.”

“Relax, or I am going to have to change this situation,” one officer tells him.

One officer asks him to cooperate, at which point McClain indicates that he is cooperating.

Watch all of the body camera footage from multiple Aurora police officers below. Warning: The images may be disturbing to some viewers.

The investigative report states that an officer is authorized to frisk a person only where “a reasonably prudent man, in the circumstances, would be warranted in the belief that his safety or that of others is in danger.”

That was not the case when Woodyard approached McClain, according to Woodyard’s own words, in which he said McClain did not appear to have a weapon.

In his interviews with Major Crime investigators, however, Woodyard appeared to contradict himself, stating, “I didn’t want to stop this guy by myself, because pretty suspicious area tied with his actions, and I didn’t want to contact somebody who I thought had weapons by myself.”

Woodyard was never asked to explain why, when the 911 dispatcher said McClain was unarmed, he believed McClain might have a weapon. Major Crime detectives also never asked him to explain his conflicting statements, according to the report.

“Based on the record available to the panel, we were not able to identify sufficient evidence that Mr. McClain was armed and dangerous in order to justify a pat-down search,” the report states. “The panel also notes that one officer’s explanation that Aurora officers are trained to ‘take action before it escalates’ does not meet the constitutional requirement of reasonable suspicion to conduct either a Terry stop or a frisk.”

The arrest

Less than 60 seconds after Woodyard first stopped McClain, he, Officer Jason Rosenblatt and Officer Randy Roedema physically forced McClain into a grassy area and — unjustifiably, according to the panel — took him down onto the ground.

That constituted an arrest and necessitated probable cause to make that arrest — which the officers did not have, the panel wrote.

“Since Officer Woodyard’s order to him to stop, the only facts that had changed were Mr. McClain’s attempt and stated intention to keep walking in the direction he had been going and his ‘tensing up,’” the report states. “In the panel’s view, none of these facts would be sufficient to establish probable cause of a crime.”

The use of force

As the three officers struggled to move McClain into the grass, Roedema told another officer McClain made a grab for his weapon.

“He grabbed your gun, dude,” Roedema says in the camera footage.

The alleged gun grab is not seen on camera, though Roedema later told investigators that McClain reached for and touched the grip of Rosenblatt’s gun, which was holstered.

From that moment on, the cameras, which shake and rock as the officers struggle with McClain, show few of the details of what happened that night. All the officers later told authorities their body cameras fell off during the struggle.

“Give us some more units. We’re fighting him,” an officer is heard saying into his radio.

The investigative report confirms that it was at that point that Rosenblatt attempted the first of two carotid chokeholds on McClain.

“In a ‘carotid control hold,’ an officer applies simultaneous pressure to the left and right sides of a subject’s neck to deprive the brain of oxygen and induce unconsciousness,” the document states.

The move differs from a typical chokehold, the panel members wrote, which is dangerous because it can restrict a person’s breathing.

“Positioned behind Mr. McClain just as he was being taken to the ground, Officer Rosenblatt applied the first carotid hold,” the report states. “However, Officer Rosenblatt stated that he released the hold after approximately one second, and once they were on the ground, after realizing that it was not going to be effective.”

The panel members wrote that officers are allowed to use potentially lethal force with there is a significant threat of injury or death to themselves or others. At the time of McClain’s death, the Aurora Police Department permitted the carotid chokehold to be used in those instances.

By the time the first hold ended, however, McClain was on the ground and the threat of an officer’s gun being taken had been neutralized.

The second chokehold

As McClain lay on the ground, Woodyard and Rosenblatt struggled to get him to be still. Rosenblatt pinned one of his arms down while Roedema applied a “bar hammer lock” to the other.

Woodyard applied a second carotid chokehold.

“Although it is unclear precisely how long Officer Woodyard applied the hold, on the body-worn camera footage an officer can be heard asking, ‘Is he out?’ and two other officers responding, ‘No,’ and, ‘Not yet,’” the document states.

Roedema told Woodyard that McClain’s eyes rolled back and his head went limp, and instructed him to release the hold.

Read the entire 157-page investigative report below.

“Once he was lying on the ground, Mr. McClain’s ability to reach an officer’s gun or other weapons was limited by the fact that Officer Woodyard was on the ground behind him, with his gun and pepper spray pinned beneath him,” the panel wrote in its report. “If Mr. McClain was no longer presenting a threat of harm to the officers, there would have been no justification for Officer Woodyard to apply a carotid hold.”

Aurora Major Crime investigators failed to question the officers about the threat they perceived McClain to be once he was on the ground. According to the report, they also failed to distinguish during questioning the threat McClain posed while standing versus the threat he posed while pinned to the ground.

Because of that failure, the record does not provide evidence of what officers perceived as a threat great enough to justify Woodyard’s carotid chokehold.

Camera footage vs. officers’ statements

The panel members pointed to multiple instances in which the statements provided by Woodyard, Rosenblatt and Roedema told a story that contradicted what video and audio footage from the scene showed.

“The officers’ statements on the scene and in subsequent recorded interviews suggest a violent and relentless struggle,” the panel wrote. “The limited video, and the audio from the body-worn cameras, reveal Mr. McClain surrounded by officers, all larger than he, crying out in pain, apologizing, explaining himself and pleading with the officers.”

He also vomits multiple times during his final minutes of consciousness.

The officers also consistently used applied pain compliance techniques and restraints “from the first moments of the encounter until he was taken away on a gurney,” the report states. The “vast majority” of the pain was inflicted after McClain was already on the ground and handcuffed.

“I can’t breathe. Please stop,” a weeping McClain says in the body camera footage after waking from the carotid hold.

An officer tells him to stop fighting or he will be shocked with a Taser.

McClain’s next words are heartbreaking.

“I have my ID right here. My name is Elijah McClain. That’s my house. I was just going home,” McClain sobs. “I’m an introvert. I’m different. I’m just different, that’s all. That’s all I was doing. I’m so sorry.”

According to the investigative report, as McClain made that statement, an officer told a dispatcher over the radio that McClain was “still fighting.”

He continues to plead with the officers, who appear to ignore his words.

“I have no gun. I don’t do that stuff. I don’t do any fighting. Why are you attacking me? I don’t even kill flies! I don’t eat meat!”

He says he doesn’t judge people who do eat meat. “Forgive me,” he says.

I just haven’t been able to share much about #ElijahMcClain. Every time I try, I’m overwhelmed with sorrow. And I struggle with knowing that I live in a world where millions are still denying both that racism exists and that we need to reimagine public safety. Elijah wasn’t safe. pic.twitter.com/RZ2kQXoPc0

— Vonnetta L. West (@VonnettaLWest) June 26, 2020

As the officers continue to talk amongst themselves, McClain appears to be pleading for his life.

“Forgive me. All I was trying to do was become better,” he pleads breathlessly. “I’ll do it. I’ll do it. I’ll do anything. Sacrifice my identity. I’ll do it.”

The officers continue to hold him down on the ground as he cries out in pain.

“I’m so sorry. Ow, that really hurts,” McClain says. “You all are very strong.

“Teamwork makes the dream work,” he says as he trails off into sobs.

He vomits in his struggle to breathe as some of the officers can be heard searching for handcuffs and body cameras lost during the struggle. He also appears to move in a way that causes the officer on top of him to tell him, “Stop.”

“I’m sorry. I wasn’t trying to do that. I just can’t breathe correctly because …,” he says.

He appears to heave again, either with breathlessness or the need to vomit.

McClain vomits multiple times from the pressure to his chest and neck. He repeatedly apologizes as he struggles to breathe.

“You all are phenomenal. You are beautiful,” he says. “And I love you. Try to forgive me.”

At this point, one officer’s body camera is back in place. It shows another officer leaning over McClain, who is being held down on his side, and asking him what drugs he is on.

“What kind of drugs did you take tonight?” the officer asks. “We need to know, OK? We need to know what you were taking because we need to try to get you treated, OK?”

McClain doesn’t appear to respond. He is no longer fighting the officers, though his heavy breathing is apparent.

“Gotta throw up, dude?” one officer asks.

“Yeah,” McClain says weakly.

“Throw up right there, OK. Don’t throw up on me, though,” an officer tells him.

The officer holding McClain down holds him higher so he can vomit on the grass.

“Get it out, dude,” an officer says.

By this time, fire medics have been called and are on their way. Other officers have also arrived to assist Woodyard, Rosenblatt and Roedema.

As McClain continues to vomit, an officer tells him to be still and that getting up would not be “good for him.” Another officer threatens to sic his K-9 partner on McClain.

As firefighters arrive, an officer can be heard on the video telling someone over the phone that McClain had done “nothing really criminal” but had been “acting kinda weird.”

Read Elijah McClain’s autopsy report below, courtesy of Westword in Denver.

As they continue to hold McClain on the ground, ketamine comes up for the first time.

“So when the ambulance gets here, we’re going to go ahead and give him some ketamine,” a firefighter medic says. Aurora police officials identified the person who ordered the ketamine as fire medic Jeremy Cooper.

“Sounds good, dude,” an officer responds. “Perfect, dude. Perfect.”

From the officers’ conversation on the scene, it’s clear they assume McClain is on a drug that gave him “incredible strength.”

Besides the ketamine he was injected with, he had nothing but marijuana in his system, McClain’s autopsy showed.

“It is not clear from the record whether Mr. McClain’s movements, interpreted by the officers as resisting, were attempts to escape or simply an effort, voluntary or involuntary, to avoid the painful force being applied on him, to improve his breathing or to accommodate his vomiting,” the panel wrote in their report.

Fire medics delayed treatment, lacked solid plan

Aurora Fire Rescue medics arrived at the scene at about 10:53 p.m., 24 minutes after Woodyard first rolled up on McClain as he walked home from the store.

Despite the knowledge that a carotid chokehold had been applied, twice, and the fact that McClain “could be heard moaning, gagging, responding to the officers’ statements, exclaiming in pain and struggling to breathe,” they “stood back and did not render aid to Mr. McClain for several minutes,” the panel found.

The first treatment they gave was the large dose of ketamine that led to his cardiac arrest.

“Further, prior to the injection of ketamine, there was no physical contact by any of the Aurora Fire or EMS personnel captured in the footage or reported during post-incident interviews,” the investigative report states.

The panel wrote that while a lot can be learned from observing, medical personnel need to do more than watch in order to provide proper clinical decision-making. The fire medics on the scene failed to perform such simple tasks as taking McClain’s vital signs.

They also failed to come up with a plan to transition McClain’s care from the police to the medics.

“Even after the ketamine was administered, Aurora Fire deferred to the police officers in decisions regarding Mr. McClain’s care,” according to the document.

The ketamine

Paramedic Jeremy Cooper is named in the new report as the person who diagnosed McClain as having “excited delirium,” based solely on the word of the police officers. The syndrome is characterized by “increasing excitement with wild agitation and violent, often destructive behavior.”

The panel pointed out, however, that McClain had not moved or made a sound for about a minute before Cooper administered the ketamine.

Aurora Fire Rescue Lt. Peter Chichuniec was also vastly off when he estimated McClain weighed 190 pounds. He advised Faulk Rocky Mountain, the ambulance crew on the scene, to draw up 500 milligrams of the sedative.

A person McClain’s size calls for 320 milligrams of ketamine.

Eight minutes after the drug was first suggested — and three minutes after it was administered — McClain’s heart stopped for the first time.

McClain’s autopsy report states that the ketamine in McClain’s system was “at a therapeutic level, but an idiosyncratic drug reaction (unexpected reaction to a drug even at a therapeutic level) cannot be excluded.”

The investigative panel concluded that both the fire medics and the emergency medical technicians were lacking in their handling of the case.

“Aurora Fire appears to have accepted the officers’ impression that Mr. McClain had excited delirium without corroborating that impression through meaningful observation or diagnostic examination of Mr. McClain,” the report states. “As stated above, during the time that Aurora Fire was on the scene, Mr. McClain’s behavior in the presence of EMS should have raised questions for EMS personnel as to whether excited delirium was the appropriate diagnosis.”

Recommendations

The panel issued a number of recommendations for the police department, including a thorough review of its training and supervision of officers when dealing with reasonable suspicion, probable cause for Terry stops, frisks and arrests.

“The speed at which these officers acted to take Mr. McClain into custody, their apparent failure to assess whether there was reasonable suspicion that a crime had been committed and the unity with which the three officers acted suggest several potential training or supervision weaknesses,” the members wrote. “The panel also strongly recommends that every Terry stop and every frisk be thoroughly documented.”

The investigators recommended that police officials review the department’s use-of-force policy, as well as its de-escalation policy. The de-escalation policy would be “significantly strengthened” if it demanded that de-escalation be required in every police encounter, where possible.

>> Read more true crime stories

A third recommendation was for a simple model or template be put in place to transition a suspect needing medical attention from police custody to the care of medics. The panel also recommended that the city review the culture within Aurora Fire Rescue to ensure that patient safety is prioritized at the same level as officer safety.

In addition, the investigators recommended that the fire department review its protocols to ensure that a complete pre-sedation assessment is completed by medics before any drug is administered.

“This assessment should include cardiac and respiratory monitoring whenever feasible, and require that a consistent process be developed and used to ensure a verbalized pre-sedation double check for diagnosis/protocol, estimated weight, equipment inventory, and a plan for expedited post-sedation monitoring,” the panel wrote.

They also recommended the city overhaul the police department’s post-incident review process — including how authorities go about referring cases to Internal Affairs.

Changes since McClain’s death

The Aurora Police Department has already made some changes in the 18 months since McClain died. The city has placed a moratorium on the use of ketamine by emergency medical staff.

There is also an ongoing debate on the use of the drug in law enforcement settings, the panel wrote.

“As the review of the sedative is underway, we urge the city to avoid replacing ketamine with other medications that pose a greater risk to patients and to medical staff,” the report states.

Colorado over the summer also became the first state to end “qualified immunity” for law enforcement, which shields police and other government workers from being held personally responsible when civil suits are filed.

McClain’s family filed a federal civil rights lawsuit last year. Besides the city, it names as defendants Woodyard, Rosenblatt, Roedema and 10 other police officers, as well as Cichuniec, Cooper and Dr. Eric Hill, the medical director of Aurora Fire Rescue.

Cox Media Group