Long before the Mariner Moose, the Seattle Mariners were in need of a mascot.

It was 1979. The Mariners were a young team. The San Diego Chicken had grown in popularity and he’d started to make appearances outside of San Diego.

According to the Mariners, their Director of Marketing and Promotions, Jack Carvalho, was thinking of new and exciting ways to get fans to the Kingdome.

Carvalho once had a fireworks night, but all the explosions filled the Kingdome with smoke. There was a golf cart designed to look like a tugboat that would bring the pitchers out from the bullpen, but the players reportedly hated it and are rumored to have destroyed it. Carvalho once hired world-famous trapeze artist Karl Wallenda for opening night in 1978, but the patriarch of the Flying Wallendas fell to his death in Puerto Rico just weeks before the Seattle gig.

Carvalho hired the San Diego Chicken to come to Kingdome games, and after the Chicken was asked to start making appearances in Yakima and Spokane, the Chicken reportedly told the Mariners to find their own mascot.

According to a press release, characters were inundating Carvalho with pitches of their own to be the Mariners’ mascot. Many were probably enticed by the possibility of paydays comparable to the San Diego Chicken.

And so, on Aug. 1, 1979, the Seattle Mariners announced the International Mascot Contest, set for Aug. 17, as the Mariners play the Detroit Tigers.

The “open invitation” was for any and all characters to perform in front of the fans and three judges. The invite also extended to the Seattle Seahawks Seahawk (not yet Blitz) and the Seattle Supersonics Wheedle, to be a part of the event.

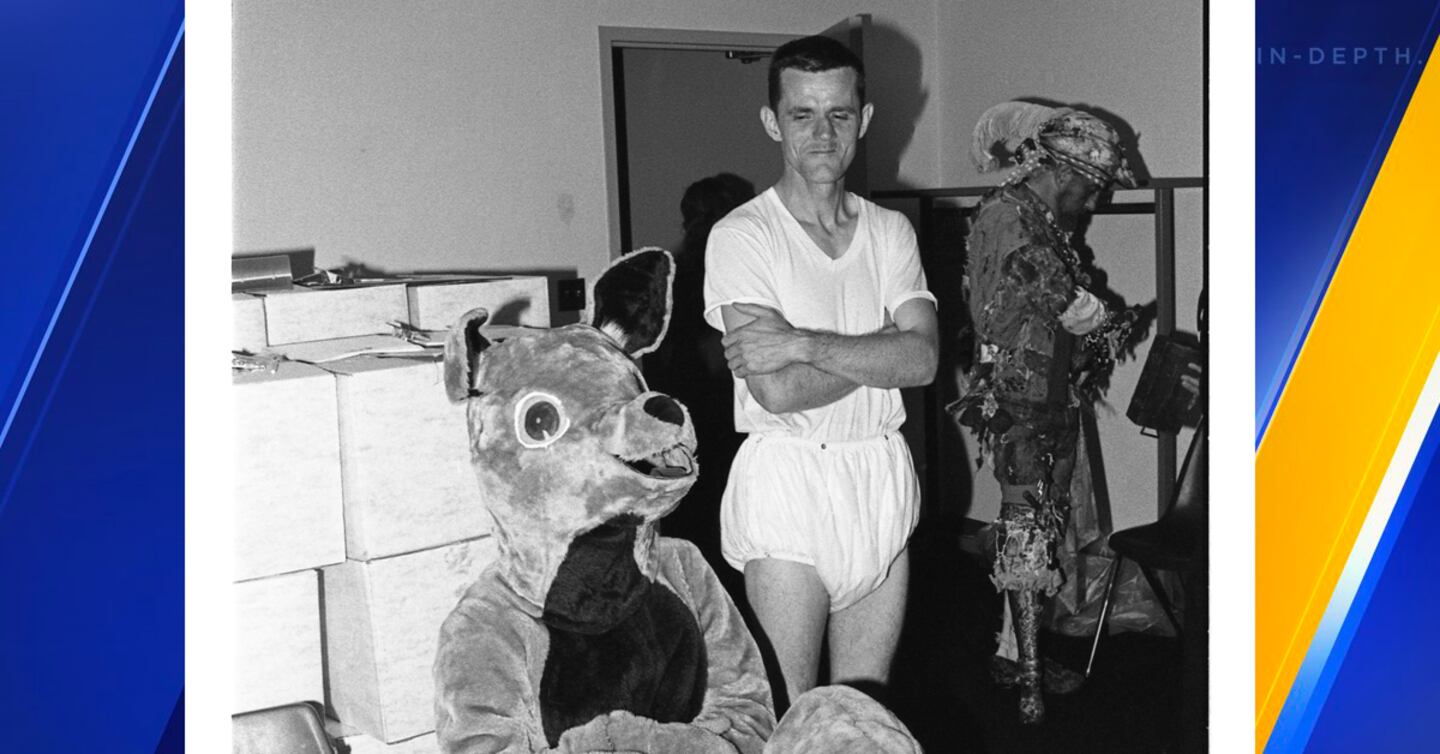

The cast of characters that arrived at the Kingdome were certainly eccentric.

There was The Fish, who may have “spawned” behind the pitcher’s mound.

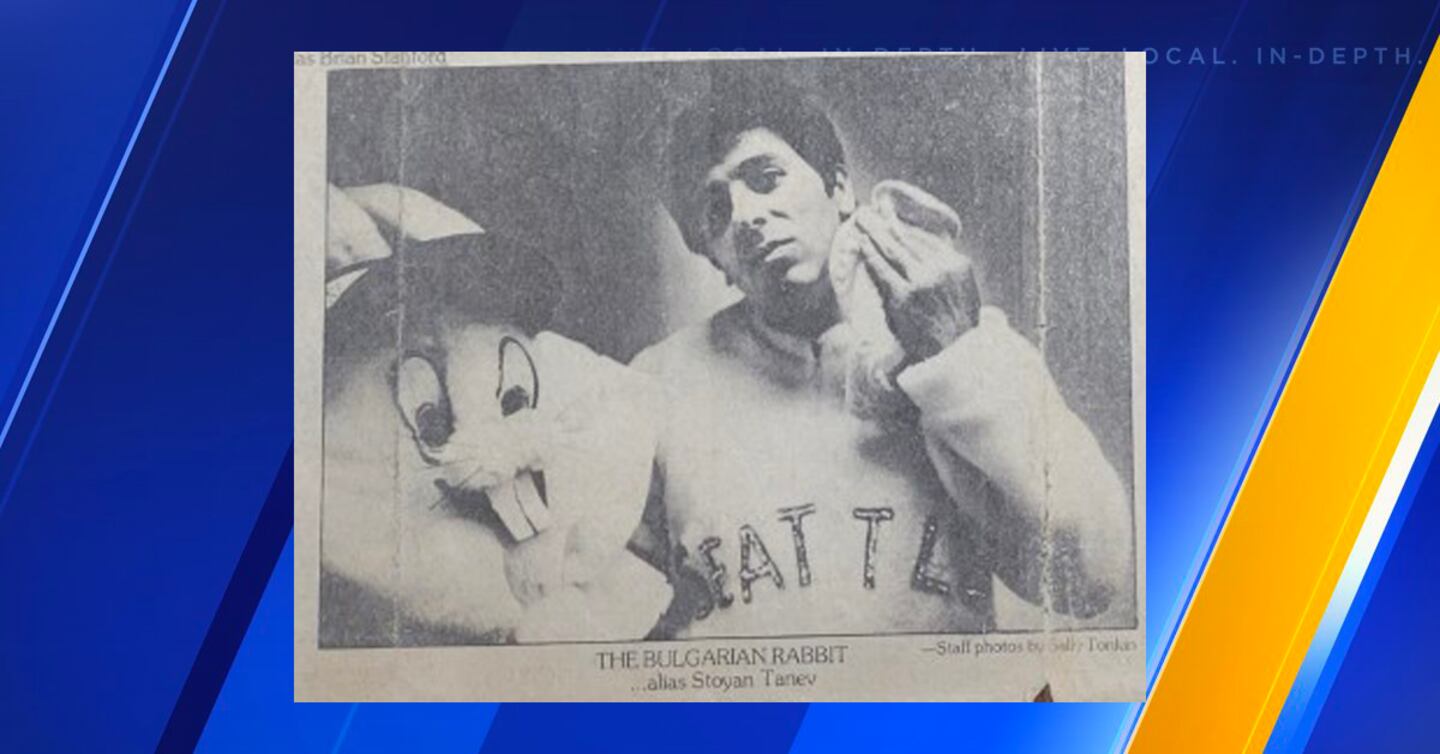

There was The Rabbit, identified as Stoyan Tanev, a real-life Ringling Bros. acrobat, who did front and back flips in a rabbit costume. Tanev passed away a few years ago, but his daughter told KIRO 7 that her father’s nickname was “rabbit” in Bulgarian.

There were several gnomes, all claiming to be a Kingdome gnome.

There was even a man dressed up as a mascot known only as the Baby. Identified as Seattle’s Fred Kenney, according to one of the judges, the Baby crawled on his hands and knees from the left field wall, only wearing a large adult diaper, all the way to home plate. When he stood up, The Baby was scraped and bloody from his arms and legs, after dragging them across some 350 feet across the Kingdome’s Astroturf.

Bruno the Bear, Big Foot, Herc and Gorty, Pelican Pete, Famie the Kanga, Mr. Murray Mouse, Sunny Deer, and many more paraded their way across the field.

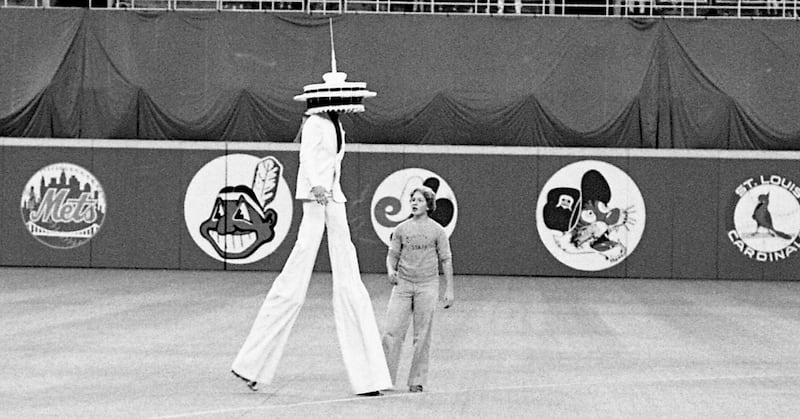

The highlight, though, was Spacie the Space Needle: A man wearing stilts with long-legged white pants (with a 62-inch inseam) and a blazer to match, wearing a replica of the Space Needle on his head.

The three judges cast their votes. The winner was Spacie, identified as Brian Keil, who won the title and $100.

There was a three-way tie for second between the Rabbit, Pelican Pete, and, yes, the Baby. Sunny Deer won third.

A former painter, Keil was comfortable on the stilts. The headpiece was homemade, while his wife Trudie helped make the suit with the long pants.

“(I) put my back against the wall of the building I was painting and right out in front of me was the Space Needle,” Keil said. “That was my inspiration.”

Spacie would go on to make appearances around Puget Sound for years, including Seafair and Sonics games.

Keil said he even walked for miles on stilts in several parades. He would win several awards and plaques in costume contests for years.

But, as time went by, Keil retired Spacie. He said there was a combination of factors, the biggest one that, while it was fun to don the headpiece and stilts, he was never officially hired as a mascot and, thus, wasn’t paid.

He would send applications and inquiries to Seattle businesses for years asking to be their mascot, but no one took him up on the offers.

Keil was even tempted to throw the headpiece in the trash, but Trudie told him not to. Instead it went into a barn, where it sat for decades.

“Whenever I’d look at it, I would think ‘Is it time to take that to the dump yet?,” Keil said.

Then this tweet happened in April.

I had no idea the Mariners had a mascot named Spacey the Needle. And was apparently retired after only a few games due to mobility issues with the stilts 😯 pic.twitter.com/sTna8H45aG

— zach (@zachleft) April 24, 2023

Pulled from a baseball bloopers tape that had made its way onto YouTube, this muted clip went viral.

KIRO 7 made inquiries to the Mariners’ Randy Adamack who helped fill in the gaps in the history of the mascot competition.

Then, as part of our research into Spacie, Seattle’s Museum of History & Industry, shared additional newspaper clippings of the event.

MOHAI showed interest in acquiring the headpiece for part of their collection. And Keil was floored.

On June 2, in a small ceremony at MOHAI, Kei arrived with the headpiece and Trudie. The Mariner Moose was even on hand for the moment.

And with slight tears in his eyes, Keil handed Spacie over and made it an official part of Seattle sports history.

And, by the way, the Mariners lost to the Tigers at that game in 1979 by a score of 9-2.

©2023 Cox Media Group